Tech house today is a somewhat divisive genre, loved by many, but loathed by some too. There’s no doubting its popularity; it’s played by DJs the world over, from Argentina to Singapore to Croydon. This is the house genre that ate all other genres, mutating, adapting, and absorbing influences. It’s traveled far from its roots in early/mid-’90s London parties Wiggle and Heart & Soul and The End nightclub. Eventually, it became the predominant sound in the mega-clubs of Ibiza and the dance music festival circuit. While a purer techno sound has regained ground over tech house in recent years, pre-COVID, tech house was still popular with clubbers worldwide.

"It was very much an attitude,

an approach to DJing."

In the Beginning: The Origin Story

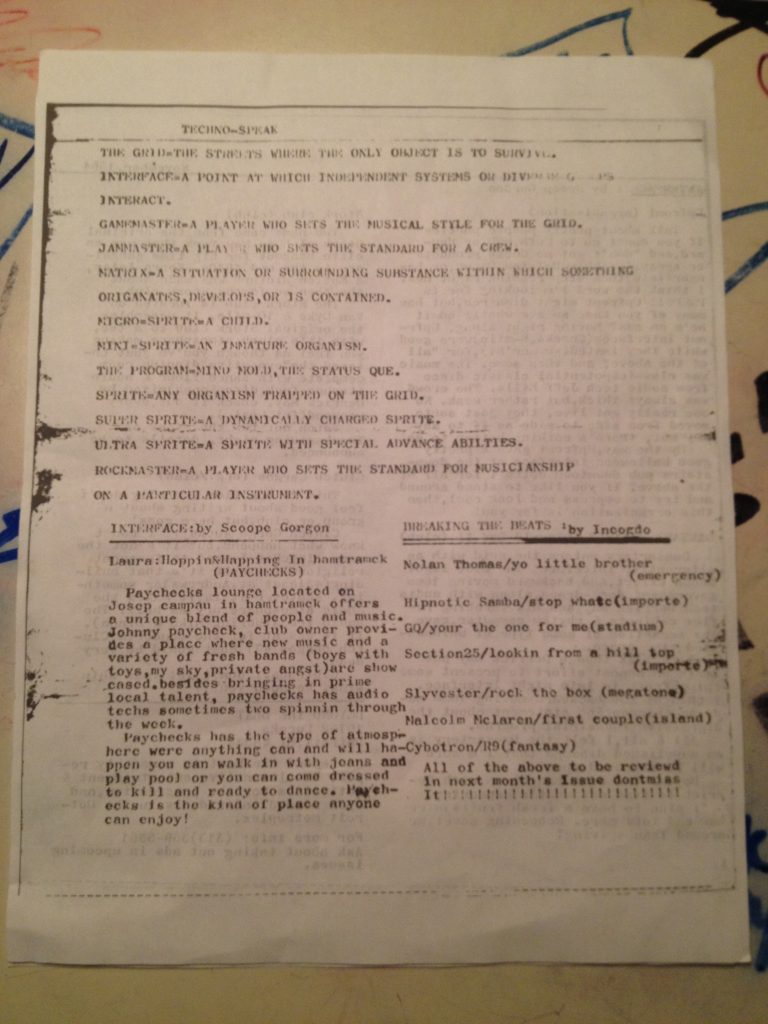

In telling a story as long and as global as this one, there will be names, tracks, and labels left out. This is simply because there isn’t the room. In addition, tech house is now a term so malleable that one person’s definition of the genre can be quite different from someone else’s. However, we can locate a starting point. In the early ’90s, “Evil” Eddie Richards, widely regarded as the Godfather of tech house, received a cassette from Mr C. On one side it said “tech” and on the other “house.” Like that, tech house was born.

Mr C picks up the story: “When the genre term started, I contacted all the other DJs and producers and said we should all call our remixes ‘tech house remixes.’ Detroit had techno, Chicago had house and I knew the media would bite.” It turns out his instincts were correct. “We all did it and the media bit immediately.”

Richards was one of three residents at the Wiggle party in London with Terry Francis and Nathan Coles. Along with Mr C, Layo and Bushwacka at The End, and the Heart & Soul, Release, and Mr C’s The Drop parties in London, these innovators were on a similar path.

Their goal was to create a new genre from DJ selections alone. Tech house wasn’t a genre of music in the early ’90s, and there weren’t any tech house records. It was very much an attitude, an approach to DJing.

As a DJing style, tech house emerged as a reaction to two factors. First, the mutation of the early U.K. acid house/rave scene into hardcore and then jungle. Second, was the increasing popularity of handbag house and its very commercial take on house music. These two trends left clubbers who wanted the early acid house vibe looking for a home.

"DJs began to play underground records that fell between the twin poles of

house and techno."

Repurposing U.S. Garage Dubs

Certain DJs began to play underground records that, in the context of a DJ set, fell between the twin poles of house and techno. They pitched down techno records, sped up US garage dubs, and found certain electro and progressive house records that somehow fit. These DJs looked sought music with that Chicago jack, tunes as emotive as the Detroit techno they loved. They used the larger context of a well-programmed DJ set to redefine certain records as part of a whole.

So tech house began as a sound that coalesced on the dance floors of a few select underground parties. This was a result of the tastes, ethos, and programming decisions of a few key DJs and the demands of their audiences.

DJ/producer and former (record shop and crucial tech house hub) Swag Records employee Dave Mothersole shares insights about that time. “U.S. labels were popular in the early days,” he says. “Murk, Astralwerks, Hardkiss, Organico, Bassex, Prescription Underground, [Canada’s] Stickman, lots of Detroit stuff and some of the jacking Chicago stuff on Relief. Big labels like Strictly Rhythm and Tribal got played too, and obscure US labels like Atlas and Index.”

"Two trends left clubbers who wanted the early acid house vibe looking for a home."

Beyond the United States

Still, the U.S. wasn’t the whole picture. “Then there was some Euro stuff,” he adds. “Mainly Dutch and Belgian, on labels like Fresh Fruit and Touché and the odd U.K. thing on Soma or whatever.” Mothersole recalls a few outliers as well. “Orlando Voorn, Steve Rachmad, and some German stuff on labels like Klang came in later too.”

Tracks ranged from the funky snares of Calisto’s “Get House” from 1995 to the Detroit-style chords and crisp beats of Animus Amor’s “And On” (1994) on Mr C’s Plink Plonk label. Janice Robinson’s “Children” (Joe T Vannelli Dub) from 1994 was an example of the kind of records being, for want of a better term, repurposed. It was dark, driving, U.S. garage dub, consisting of a funky b-line, a stab, relentless rolling beats, a few vocal snippets, and a lush pad breakdown.

Flybaby’s “You Must Admit” on Formaldehyd (1993), with its restrained chords, insistent stabs, and squelching 303 drop, was a standout. It crossed the boundaries between genres and picked up plays in the early days. Detroit was a big influence too, with lots of deck-time given to older Transmat and Metroplex classics.

"Tech house was a fiercely underground scene that rejected the tropes of the crossover sound."

What It Is and What It Isn’t

Tech house was a fiercely underground scene that rejected the manipulative tropes—big piano breaks, euphoric melodies, and diva vocals—of the contemporary crossover sound of uplifting and handbag house.

Tech house DJs used a subtler palette and generated emotional content using elements more nuanced than major-chord arms-in-the-air breakdowns. From its inception, the scene defined itself as much by what it wasn’t—trance, handbag, hard techno, hard house—than what it was. Mothersole also notes that two distinct sounds emerged in the early/mid-’90s. Wiggle concentrated on raw, stripped-down rhythms while Heart & Soul went in a more Detroit and breaks direction.

A Sense of Community

In its focus on the music rather than the DJ, warehouse locations, and sense of community, the U.K. tech house scene carried the torch for the best of acid house. It did so while jettisoning that movement’s worst excesses. Tech house emerged as a stripped-down, updated version of the egalitarian rave ethic. The scene dedicated itself to the finest underground music, handpicked from across the 4/4 spectrum.

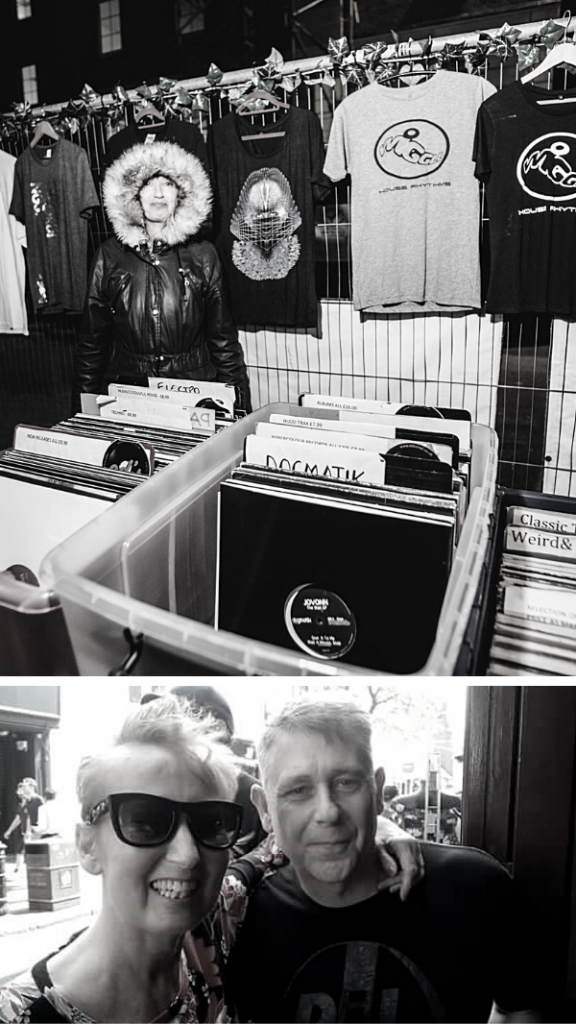

Record shops were crucial in the growth and spread of the genre too. The much-missed Liz Edwards ran the Swag Records shop in Croydon which became a vital center in the emerging London tech house scene. Producers and DJs like Francis, Jazzy M, Richard Grey, Grant Dell, and well-known names like Colin Dale and Carl Cox all served behind the counter.

"What started as an approach to DJing morphed into a genre, with rules and boundaries."

From An Attitude to a Genre

It was only a matter of time before producers and DJs began to make music specifically defined as tech house. Swag Records became home to several tech house labels. These included Swag, Funknose, Surreal, London Housing Benefit, Pirate Radio, and Uhuru Beats.

They hosted U.K. trailblazers like Asad Rizvi, the Strangeweather crew, Gideon Jackson, Richard Grey, Spincycle, Mothersole and Bushwacka as well as the Wiggle DJs and many others. Tech house labels sprang up around the world, and more promoters began to put on tech house parties.”

Rule and Boundaries Emerge

By the late ’90s, what had started as an approach to DJing had morphed into an actual genre, with certain musical rules and boundaries. During the mid-to-late ’90s first golden age of tech house, various U.K. labels staked out their interpretation of the sound.

See, for example, the back catalog of Surreal, Reverberations, and Drop Music. Others, like the superb U.K. techno label Pacific, simply happened to be releasing music that fitted the template. By the early ’00s, the U.S. was contributing large quantities of dance-floor-ready tech house too. This came via imprints like Red Melon, Tango, Detour, DoubleDown, Movim, and others.

"At the start of the 2010s, the tech house template was set to conquer

dance floors worldwide."

2000: A New Decade

The 2000s saw the birth of dubstep, grime, electroclash, and the steady resurgence of minimal techno and progressive house. Of these, it was only minimal and progressive house that had much impact on tech house. For a decade, tech house simply absorbed the influences around it and grew ever bigger. Producers like Tiefschwarz, Booka Shade, Luciano, Rodriguez Jr., Steve Bug, and many others all developed their takes.

Many pioneered a more synth-based, European-flavored sound that proved extremely popular. M.A.N.D.Y. vs Booka Shade’s 2005 classic “Body Language” represented a codification of the sound. It was a clean, restrained, and efficient distillation of certain elements of the tech house template. Likewise, Steve Lawler’s “21st Century Ketchup” from 2008 epitomized a more minimal influenced take on the genre, ideal for big rooms.

At the start of the 2010s, the refined tech house template was set to conquer dance floors worldwide. The Hot Creations and Toolroom labels, among others, continuing the process of defining global tech house and taking it to the masses. DJs like Solomun, the Martinez Brothers, Patrick Topping, and Marco Carola embraced this streamlined take on tech house. Its effective synth riffs and simple basslines slowly took over Ibiza.

"As tech house went global, it peaked.

This irony was not lost on many of the original players."

The Rise and Fall…and Rise Again?

Inevitably, as tech house went global, it peaked. Over a period of years—exactly which years depend in part on your taste in house music—the genre narrowed into a set of production tropes. While hugely successful, these eventually began to feel a little tired. From those first trail-blazing labels and tracks back in the ’90s, certain musical ideas became hackneyed. This was the case with the “bmm-tss-bmm-tss” Chi-town drums, stripped-down tracks, polished percussion, and relentless techno bass lines.

As more producers took to creating that particular sound, imitators imitated imitators. As a result, much of the genre became homogenized. This sidelined the subtle variation and broad influences characterizing the original movement. This irony was not lost on many of the original players who had created the scene in the exact opposite spirit.

A Slow Distillation

Tech house, through its global popularity, slowly distilled down to a set of repeatable ideas and in the process, it gradually lost much of what had originally made it exciting. For many producers and DJs, it simply became a funky hat-loop, a two-note bassline, an arrangement, and little more.

Originator Terry Francis: “It just got bland really. I was never a great lover of the term tech house anyway. The idea of tech house was never formulaic; it could be breakbeat or deep or whatever. It just had to have a certain groove to it. Now it seems to be loopy and formulaic rather than free.” By the mid-2010s, a media and popular backlash against tech house had begun.

"The true legacy of tech house is,

much like its original spirit,

something both subtle and special."

A True Legacy

But it wouldn’t be fair to say that there’s no good tech house around anymore. There’s quality music in every genre and there’s still plenty of great tech house around if you’re prepared to look for it. It remains the sonic weapon of choice for many parties worldwide and for many DJs, a few choice tech house tunes can work a treat in sets that encompass other flavors of 4/4.

However, there’s little doubt that tech house has, at least for the moment, creatively peaked, After twenty-five years, the vague area that lies between techno and house is thoroughly mined for ideas. Perhaps too much experimentation in that middle ground has led to a popular resurgence in a more purist house or techno approach. Maybe things will circle around again.

The true legacy of tech house is, much like its original spirit, something both subtle and special. DJs reacting to audiences defined the genre. It was born in a community of dancers, DJs, producers, record shops, and promoters, created in the ashes of acid house.

For a few years, it demonstrated how powerful a community-led scene can be. Whatever your opinion of this week’s tech house releases, the genre remains a clear example of the power committed DJs and clubbers have to drive and shape musical development.