The Aerophone Brisa is an advanced digital wind synthesizer that gives flutists and wind doublers a sound palette never before possible. Blending a traditional flute design with 100 expansive onboard tones, Brisa commands the stage. Five versatile woodwind players experience the Aerophone Brisa for the first time and share their initial impressions.

Table of Contents

Lorren Chiodo

Lorren Chiodo is a dynamic Australian saxophonist, vocalist, composer, and music director renowned for her vibrant stage presence and genre-spanning artistry. Chiodo’s distinctive tone and melodic improvisation have led her to perform and record with numerous notable artists, including Harry Styles and UMI. Shed has appeared at Coachella and recorded for film and TV.

Could you give me some background about your musical journey?

I’m from Australia. I’m a woodwind player—primarily saxophone and flute—and a music director, composer, and producer here in LA. I went to Berklee College of Music in Boston. I’ve done music editing for film and TV. I’ve toured with Harry Styles. I just toured UMI opening for Jhené Aiko and music-directed for PinkPantheress.

How do you currently use electronics in your practice or performance?

I use them a lot, especially the Aerophone. I used that on my last arena tour; we mixed flute and saxophone with BOSS pedals. I have pedal boards running through my acoustic instruments, and I also have the Aerophone running through a different board, doing auxiliary and synth parts in pop-R&B music. I also have a solo project where I use live looping, live effects, and sound design with my flute and sax, all through pedals and processing.

What’s your first impression of Aerophone Brisa?

It’s sick. I love it. I’m always a fan of making woodwind things cool and relevant and doing things they don’t usually do.

How would this instrument enhance your practice or performances?

Practice-wise, it’s good to be able to practice in hotel rooms and late at night, not having to worry about making a sound, so that’s always sick. It adds an extra element to live performance and gives artists options on the road. It’s not just a flute sound; you can experiment and get more options and new ways to do things.

Do you have any advice for other wind players who are interested in trying this out?

I would just say try it out. Just try it. Try what you think is cool, experiment, and don’t think there have to be rules that you don’t have to break.

Braxton Cook

Braxton Cook is an Emmy and multi-Grammy-nominated alto saxophonist, vocalist, and composer celebrated for his unique blend of jazz with soul, R&B, and hip-hop. A graduate of Juilliard and a former member of Christian Scott’s band, Cook has released several acclaimed solo projects.

He has performed on renowned stages worldwide, such as Coachella and NPR’s Tiny Desk, and has contributed to major media productions, including Pixar’s Soul and Vox’s Earworm series.

Could you give me some background about your musical journey?

I grew up in a musical household. My mom played classical piano, and my dad used to play a little trumpet back in high school. I grew up listening to a lot of Motown, gospel, and jazz music. At about 10 years old, I played a little recorder, learning “Hot Cross Buns” and the fingerings.

I first wanted to play the saxophone because my dad played. I heard him practicing in the basement. I became enamored with the sound. He let me try, and I got a decent sound out of it. It didn’t squeak, which most kids would do without knowing the armature. I was like, “Okay, I like this!” In fifth grade, I signed up for band on saxophone. All the other kids were talking and chatting, and I was really into whatever we were playing. Then, I discovered jazz band. I had on Charlie Parker for the first time and became obsessed. The summer between 8th and 9th grade, I put in a lot of hours practicing, transcribing, and studying music.

By my senior year, I was convinced music was what I was going to do. From there, I went to Georgetown, then Juilliard, met Christian Scott, and toured with him. I’ve been traveling the world as a full-time musician since I left home. Eventually, I stopped playing so much as a sideman. I wanted to put out my own music around 2017-2018. It snowballed into record after record.

How do you currently use electronics in your practice or performance?

I use it a lot in my practice. That’s how I write, produce, and create a lot of my songs. Almost everything starts as a demo of some sort; it could be a drum loop or something that I build a tune on. Even my instrument or jazz tunes start that way, it’ll be like a loop, I improvise over and record ideas, edit later, and come up with tunes. I do a lot of production on my laptop. Eventually, I take those demos and ideas and bring them to the band, and then we workshop things.

On the live side, I have a pedal set up. I have a delay, reverb, and have used the BOSS Octave pedal. I like the sound of a lower octave on the alto. It sounds a little fuller. My band uses live tracks on certain things and sometimes samples, so we use the SPD pad. That’s a huge part of our sound, because we’re trying to blend R&B sounds and more progressive jazz elements with acoustic elements. I have some parts of my set where I’m playing saxophone, then my drummer, Curtis, will play the SPD with a pedal that triggers a big 808 drop. When used correctly and strategically, it’s nice to have those elements in the show.

What are your first impressions of Aerophone Brisa?

It looks damn good—like a flute! I wasn’t expecting the actual key work from a flute. It looked like they pulled the keys off a flute, so that was really surprising in a really good way. I think a lot of flute players and musicians—doublers alike will love that.

Is it intuitive?

Absolutely, I understand it. The trickiest parts for me were the bridges and the octaves. Which, with wind instruments, that’s kind of a thing. The AE-Brisa was my first time ever playing an electronic wind instrument. Once it was switched to the saxophone setting, I was like, “Oh, this is great. I get this.”

How could you see it enhancing your practice or performances?

It would be a really cool moment in the set to do something featuring the flute. I think people would be like, “Woah, what is that?” The crowd loses their mind if I take out a guitar for one song. They just expect the saxophone; that’s what I’ve done most of my career. I’ve been playing the flute since I went to Juilliard. It’s required. But people don’t know that because I didn’t necessarily showcase it live. However, I’m doing it more, so I plan on utilizing it in the set and giving it its proper moment. That’ll be impactful and will push me to do more featured moments in the set, so it’s not always like the entire band playing the whole time.

Do you have any advice for other musicians who are interested in trying it out?

Practice your flute, man. If you’re a saxophonist and don’t play flute often, practice your flute. It’ll get you honest. Because it’s electronic, those in-between notes won’t come out clearly on the electronic instrument. So, your fingerings have to be more exact between a G and a G sharp or whatever it is. Certain things that fly on the acoustic flute don’t work on this, and it will force your technique to clean itself up.

James King

James King is a versatile American multi-instrumentalist, best known as the saxophonist and co-founding member of the soul-pop band Fitz and the Tantrums. Born in Los Angeles, King’s musical journey began early; he started learning guitar, violin, and piano before focusing on the flute at age nine and adding the saxophone at eleven.

He co-founded Fitz and the Tantrums alongside Michael Fitzpatrick, and his baritone saxophone became a defining element of the band’s sound, featured prominently in hits like “Out of My League,” “Fool,” “HandClap,” and “The Walker.”

Could you give me some background about your musical journey?

I started music as a small kid. My mother is a classical cellist, and my father was a jazz guitarist. I grew up learning the classical approach and listening to a lot of jazz, classical, and pop music. And my dad roped me into his cover band pretty early on, so from age 13, I was playing bar gigs. He would sneak me in, and I’d have to learn covers. I’d only been playing sax for about a year, so I was just a kid learning. But I knew enough that I could play “Night Train” or “In the Mood” or something like that.

I went through legit saxophone training in addition to my flute lessons. I totally immersed myself in bebop and jazz playing. I went to LA County High School for the Arts, where I was lead alto sax and was just starting to play other saxophones and styles. I went to CalArts for my undergrad in the early ’90s and was a jazz performance major.

I focused on becoming a well-rounded player. As soon as I left school, it was the swing revival, so I was playing in swing cover bands, and then ended up sort of in the funk scene and went on tours with reggae and ska bands.

Then my recording career started, and I did a bunch of records with Breakestra with some other artists. I started branching out, writing and collaborating with a lot of people whom I had gone to school with. Michael Fitzpatrick, the leader of Fitz and the Tantrums, is an old college buddy of mine. He wrote some songs, and we got in the studio and formed the band. And I introduced him to the other vocalist, Noel. We were signed and in the trenches as a band, touring, and then up to having radio hits and being a national touring act.

I’ve been meeting as many kinds of musicians as I can. I’ve done some contractor calls for symphony gigs, backing Café Tacuba and Tony Bennett. Gradually, in the LA scene, I’ve connected with a lot of producers like Lon Bronson, Andrew Watt, and others who are in the hip-hop world—Big Daddy Kane and EPMD. I played the solo on the M83 song, “Midnight City,” and I was on a Rolling Stones record a couple of years ago. Now, I’m getting into scoring and studio writing for cartoon animation.

How do you currently use electronics in your practice or performance?

It’s pretty utilitarian right now. If I can approximate a sound that I’m hearing, I’ll do it as a temporary thing. My stage rig is an acoustic digital hybrid world, because I’m playing a lot of saxophone, but I’m also playing a ton of keyboard patches and triggering samples that are on the record for playback. I haven’t really bothered getting great at synthesizing as a producer. If the sample is there, I’ll use it. If it’s not, I’m just going to move on.

What were your first impressions of Aerophone Brisa?

The Brisa was a little hard for me to handle at first with the responsiveness, but after I sat with it for just a few minutes, I was able to zero in on what it needed from me to make a sound. Once I wasn’t trying so hard to support it as if it were an acoustic flute, then I could experiment with digital sounds in a way that isn’t usually as quick for me to do on a keyboard.

How would this instrument enhance your practice or performances?

As a touring musician, it would be really useful to have as a practice tool on the road and as a performance instrument on stage. It would be totally unique and translate well to an audience. To see someone assuming the flute position and whatever sounds come out would be a huge benefit to the live show.

Do you have any advice for other musicians who are interested in trying it out?

Bring all your flute technique to it, forget it, and have fun. It’s a pretty intuitive instrument right off the bat. If you have any sort of flute experience, it is going to be really fun. It would be a useful addition to the live rig and the studio. As a melodic player, I think in melodic lines more than I think in choral composition and improvisation, and so if I’m coming up with a line, it’s useful for me to have that tool handy in a studio where I can just trigger a sound that I want right away instead of have to do it acoustically and then translate that to production.

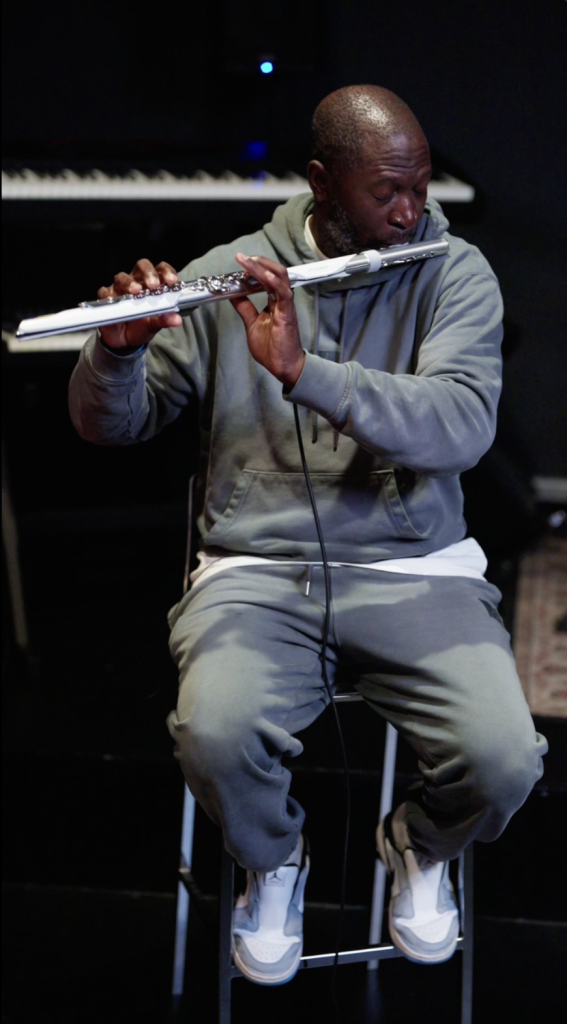

Mike Phillips

Mike Phillips is a world-renowned American saxophonist celebrated for his electrifying performances and genre-blending artistry that fuses jazz, R&B, hip-hop, and soul. He was born and raised in Mount Vernon, New York, where he was surrounded by a rich musical environment from an early age. Phillips is uniquely distinguished as the only musician to have recorded and toured with legends Stevie Wonder, Prince, and Michael Jackson.

Could you give me some background about your musical journey?

I started with Stevie Wonder at almost 18 years old. I was on tour with Stevie, and then I was the second artist assigned to a label called Hidden Beach that Michael Jordan owned. Jill Scott and I were the first artists there. Michael signed me as the first-ever musician to have a shoe deal with Nike, which was still crazy for me. And then I went on and toured with Prince, Musicology Live 2004ever. Then, I recorded “Behind the Mask” with Michael Jackson, which is probably the only song in his repertoire that features a sax player. With each experience, I’ve had the opportunity to learn, grow, and morph, reinvent, and chase a level of technical facility because I’m still fascinated with being a better player. The journey is ongoing, which is beautiful.

How do you currently use electronics in your practice or performances?

I played the Aerophone. I was the first person to take a wind instrument and have it turn into a talk box. I think that was in ’89. I was always encouraged to find a way to get into the digital domain, even when the technology wasn’t good. Michael Brecker told me, “Mike Phillips, you’re a bad boy. Let’s keep the technology rolling.” He went ballistic when I showed him that I was using it as a talk box.

Knowing that Michael Brecker, one of the preeminent saxophonists of all time, who also dug into technology, knew about me and what I was doing in the digital domain, really made me so excited to really champion this effort to make sure our musical perspective can be in the digital form. We can still feel as valid as woodwind players, but we are still getting into the world of VST, which is beautiful. And Roland has taken the bull by the horns and has made strides within the last seven years that nobody had done. Everybody’s sitting around watching us now.

What are your first impressions of Aerophone Brisa?

First, it’s beautiful. Second, it translates well. And third, the response is immaculate. You can’t ask for all three of those things. I’m at a point in my life where telling people what doesn’t exist or what it isn’t, isn’t really in my spirit. If you don’t have anything nice to say, don’t say it. But it works the opposite. If you have something nice to say, speak on it. Yell it on the mountaintop. This thing is a game changer for musicians who are used to the response of a woodwind instrument.

Did you find it intuitive?

I can’t blow flutes correctly, so they always give me a headache. But this takes the technical jargon out of what a flute requires. It responds to the embouchure beautifully. Now, I just need to get used to it and shed on it, and it’s going to be beautiful. The sounds and the response as a standalone unit are going to be great. It has the possibilities for everything from pedals to diving into your own computer.

It can be so flexible, and now the creators can do what they want to. You can’t do what you want to if the instrument isn’t up to par. So now that we have something that really resonates in the woodwind domain, but also the digital domain, and how those two worlds are cross-pollinated to the point where now we can play it by itself and it’s good, or we can go all in with every pedal known to man.

I’m happy for the flute players. Saxophones, we’ve been loud. And I think flute players are gonna come get us back because now they can turn up. Now, they can get a guitar sound and shred. I think flute players are going to be coming for our heads. There’s gonna be a flute revolution.

Do you have any advice for other musicians who are interested in trying the Brisa?

This is the closest to the flute and woodwind experience as you can get, because now you have the actual key shape, like the flute C. The spring action is as close as you can get it in the digital space. My advice is to play chromatic scales and get used to the unit. Get your fingers used to the pressure that comes with it, because it’s not pushing back as hard as a flute would. My other thing is the expectations—this is not a flute, but this is the closest thing in the digital domain that will give you that feeling, so you can start doing some digital things with that instrument.

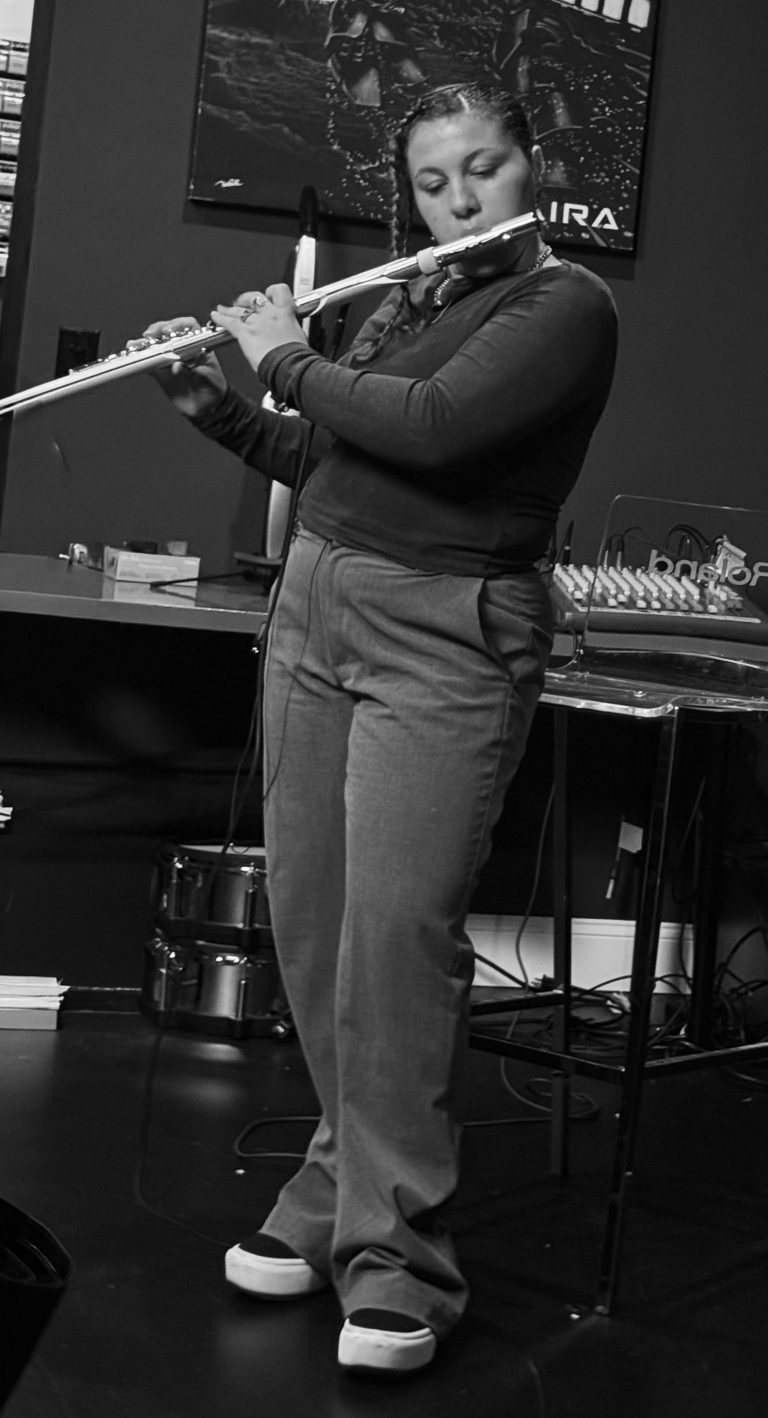

Elena Pinderhughes

Elena Pinderhughes is an esteemed flutist, vocalist, composer, and songwriter known for her unique blend of jazz, hip-hop, and R&B influences. Born in Berkeley, California, she started playing the flute at seven years old and recorded her first album, Catch 22, when she was just eleven.

In addition to her performance career, Pinderhughes has also worked on film scores, collaborating with composer Laura Karpman on the Academy Award-nominated score for American Fiction.

Could you give me some background about your musical journey?

I started playing flute when I was about seven years old. Growing up, I was fortunate to have an amazing music program, and I started performing and touring pretty young. Then I moved to New York and had the opportunity to join some really amazing bands with Christian Scott—now Chief Adjuah. I’ve played with Robert Glasper, Herbie Hancock, Future, and different folks. I do many genres, but I specialize in jazz, hip-hop, and R&B, and I also do quite a bit of playing and writing for film scores.

How do you currently use electronics in your practice or performance?

I use them sometimes live, depending on the situation, and then quite a bit in the studio as well. I’m just diving into my pedal journey. In the last year, I’ve become more familiar with them, and it’s been really fun. I’ve been experimenting with different delays, reverbs, sonics, and a little looping and chorus effects.

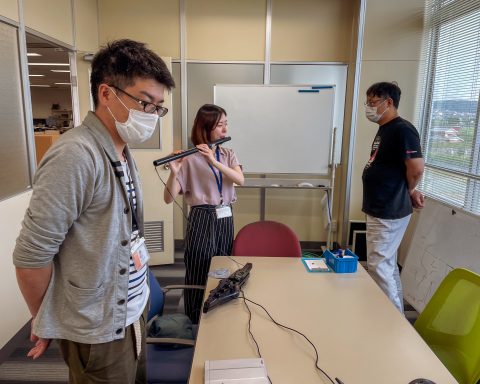

What were your first impressions of Aerophone Brisa?

I thought the Brisa was awesome. It’s the most comfortable I’ve felt on an electronic instrument, and it made me really excited to have so many possibilities of what I can do on an instrument that I’m so familiar with. It made me excited to dive in more.

Did you find it intuitive?

I found it super intuitive. The only thing I had to figure out was the embouchure, but outside of that, it felt just like a flute.

How do you think this instrument would enhance your practice or performances?

It would allow me to add more layers to a live experience and record different layers faster than I would on the piano. You can play in different settings. For gigs where an artist wants to match the sample or sound, you can program and play those exact sounds. It’s like the way a keyboard player can program that sound right in. You can do the same and play it exactly how it was on the record, or exactly how it’s meant to be delivered every time.

Do you have advice for any wind players who are interested in trying the Brisa?

Definitely try it! It is an amazing way to step into electronics with a familiar approach. Dream bigger about what a flute can do because the possibilities are really endless with something like this.