Prince Paul was not only the sonic architect behind De La Soul’s most seminal albums from 1989 to 1993. He also paved the path for producers like Madlib, J. Dilla, and others who find comfort left of center. While his peers were scouring the soul and jazz sections at record stores, Paul was perusing the world and folk genres. The results were warped yet funky playgrounds that invited rappers and listeners to allow their imaginations to run free. “Some people see music in colors,” he says of his approach. “I see music in pictures. I try to make everything visual. The skits came from that, concept records came from that.”

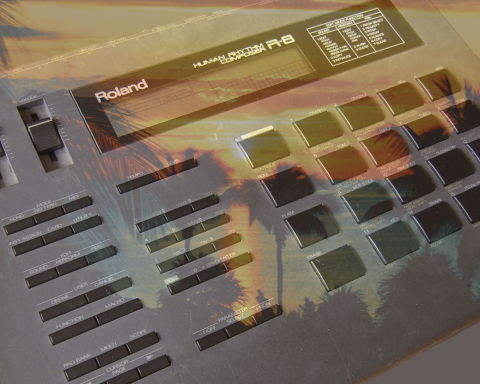

Whether using the Roland TB-303, TR-606, TR-808, or the rare BOSS DR-55 Dr. Rhythm, which Paul affectionately calls “the first programmable drum machine,” the brilliant producer left his sonic fingerprints all over hip-hop. He shares insights about the technology and techniques behind some of his landmark productions.

Playlist

Oodles of O’s by De La Soul

After being boxed into the “hippie rap” label following the success of its kaleidoscopic 1989 debut, 3 Feet High and Rising, “Oodles of O’s” saw De La Soul hitting back. On this grimy, lo-fi opener to De La Soul Is Dead, Paul modulates the bass tone from “Diamonds on My Windshield” by Tom Waits while De La guides listeners down a syrupy stream of consciousness.

On a Paul track, everything from James Brown’s “Funky Drummer” grunts to interpolations of Crash Crew’s “On The Radio” can appear at any time. That hodgepodge of sonic influences is Paul’s trademark. And it was aided by changes in the production technology landscape. “It was looped on a SP-12, but the technology had changed,” he says, “so I used an S950, which had a little more sampling time and features.

On Fire by Stetsasonic

While he’s not credited as the creator of drum and bass, Paul challenges anyone to find a song with the genre’s signature frenetic hi-hats that predates the title track of Stetsasonic’s 1986 debut. “It was a mistake. I thought, ‘No one is freaking the hi-hats like this,” he proudly states. “I might be the first one to tap into that, you gotta show me a record that did the same.”

It isn’t far-fetched to think that Paul’s penchant for exploration landed him on uncharted musical shores. This is especially the case when we learn he originally created the beat on the analog TR-808, which could not store data externally. He had to recreate the initial moment of creative spontaneity by listening back to a cassette recording of the magic moment.

"No one is freaking the hi-hats like this. I might be the first one to tap into that, you gotta show me a record that did the same.”

It’s a Big Daddy Thing by Big Daddy Kane

As a student of music history, Paul’s production often consists of snapshots of the current era or mosaics of multiple generations. The sped-up horns of Otis Redding’s “Swingin’ on a String,” pulsating bass from Larry Davis and The Marvels’s “The Magic Is Gone,” and big band stylings of Pat Lundy’s “Work Song” span the ’60s and ’70s, giving Big Daddy Kane a retro-futuristic soundscape to tap dance all over lyrically. Realistic HR-16 drum sounds paired with the TR-808’s tried-and-true kick made a thunderous combination that showcased Paul’s talents for electrifying dancefloors.

If you pay rapt attention, you can also hear a part of hip-hop history Paul kept in the song. “When Kane goes, ‘Because it’s a big daddy thing,’ if you listen closely, he had so many chains on you can hear them rattling when the music drops on that last line.”

"If you listen closely, he had so many chains on you can hear them rattling when the music drops on that last line.”

Constant Elevation by Grave Diggaz

Although he doesn’t have a credit on the song, Grave Diggaz’s “Constant Elevation” wouldn’t have its grim bounce without Biz Markie. That menacing bassline loop from Allen Toussaint’s “Louie” was also repurposed by Markie for his 1991 track “Let Go My Eggo,” released three years prior. In a move that exemplifies the unwritten rules of hip-hop production in the ’90s, Paul couldn’t use the same sample unless he added a twist all his own.

“I remember coming up with that loop, and right about the same time that I was putting it together, Biz Markie had the same thing,” Paul recalls. “I had to flip it differently. You can have the same loop, but you don’t want to do the same thing with it.”

Steady Slobbin by Prince Paul

Paul was bound solely by the limits of his imagination. Thanks to the sampling capabilities of the ASR-10 and the drum patterns offered by the SP-1200, he turned his appreciation of Ice Cube’s “Steady Mobbin’” song into a parody record.

Not many herald this track from his second solo album, A Prince Among Thieves, as one of his best. Still, it’s truly a quintessential look into the creative curiosity and self-imposed challenges that allowed him to push the boundaries of hip-hop production. “I listened to that song and thought, ‘I could make a parody of that beat,’” Paul explains. “I would listen and be like, ‘I don’t know where he got that from, but I know where he got this from. I had to make stuff up to sound like his. I wanted to sound like his, but different.”

Me Myself and I by De La Soul

No song encapsulates the collaborative, fun spirit of De La Soul like the group’s only song to top Billboard’s Hot Rap Songs chart: 1989’s “Me Myself and I.” Paul produced the funky house party anthem using an SP-12 and S900, but the entire group conceived it. “The main loop is Parliament-Funkadelic. One guy suggests we use a certain part of the record, and one guy has a hook. Maseo says, ‘I got the scratches,’” he explains. “Those records are so layered and textured because we tried everything.”

"One guy suggests we use a certain part of the record, and one guy has a hook. Those records are so layered and textured because we

tried everything.”

Men in Blue by Prince Paul ft. Everlast

Taken from his second solo album, A Prince Among Thieves, this rock-rap storytelling track is told from the perspective of a tyrannical police officer played by Everlast. The song remains near and dear to Paul’s heart because it showed the world he wasn’t only adept at manipulating other musicians’ sounds. He was also skilled enough to pick up an instrument and create greatness on his own.

“I played the bass line on a bass guitar. The drums might’ve been an RZ-1,” Paul reveals. “It showed I could sample, but I also played the bass guitar, even though it’s minimal. That was a source of pride.”

Booty Clap by Prince Paul

Mimicking the booming 808 kick, fast tempos, and vulgarity of Miami bass, on this track, Paul tuned 808s to play a melody. By 1996, when he crafted this beat, Paul could bend any sound to his will and evoke exactly what he heard in his head. The innovative twist on the sound of Miami bass pioneer Uncle Luke displayed the Grammy Award-winning producer’s diversity.

“To me, it’s the first time I heard a fast drum beat with tuned 808s,” he proclaims. “I made this in 1996, and I can’t think of a song before that that had tuned 808s as the main drum beat.”

Fun fact: Paul’s late mother wasn’t a fan of the song’s subject matter, but the beat was so infectious it became her favorite song from her accomplished son.

Ring Ring Ring (Ha Ha Hey) by De La Soul

Like “Oodles of O’s,” the bluesy bounce of De La Is Dead’s first single was an intentional departure from the “hippie rap” style the group felt pigeonholed in. “It was coming up off of a time where we had a hippie vibe. By the time we got to De La Soul Is Dead, we tried to strip that persona and marketing plan the label had,” he says of the group’s reactionary follow-up release. “That song showed we could go from the ‘Me Myself And I’ vibe and go a bit mellow while still retaining that sound.”

“I said, ‘I’m going to take all the elements of the 808–the bongos, hi-hats, the kick, the snare.' That song uses every bit of the 808.”

Do as De La Does by De La Soul

So much of hip-hop production is dependent on the technology of the time. “Do as De La Does” was Prince Paul proudly bringing nearly every sound feature on the Roland TR-808 to life. The rattling hi-hats, sparkling congas, and crisp snares all came from Paul’s masterful manipulation of a Roland machine his contemporaries used for single sounds rather than a suite.

For Paul, this is one of the crowning achievements of his legendary hip-hop discography. “I said, ‘I’m going to take all the elements of the 808–the bongos, hi-hats, the kick, the snare,'” he remembers. “That song uses every bit of the 808.”