By early 1980, hip-hop was infiltrating every borough in New York City. Bass-heavy sounds emanated from boomboxes around the city and captivated the youth. Kangol hats, Adidas shell toes, dookie gold chains, and Puma tracksuits signaled a culture shift. From the disco-infused beats of Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five and the hard-hitting boom bap of Run-DMC to Egyptian Lover’s smooth electro and the gritty anthems of N.W.A, the creativity pouring out of the decade was fresh and exhilarating. As the decade ended, the boundaries got pushed further with De La Soul, a group that espoused peace, love, and harmony in its aesthetic and lyrics. The following ten songs helped define the era and remind us repeatedly why the 1980s were such a pivotal period in the genre’s development.

Playlist

That’s The Joint by Funky 4 + 1 (1980)

MC Sha-Rock was just 16 when she became the first female MC to rock the mic on national television. It was February 1980, and Blondie frontwoman Debbie Harry had invited Sha-Rock’s group, the Funky 4+1, to appear on Saturday Night Live. Donning a baggy red t-shirt to conceal her baby bump, Sha-Rock stepped on stage for a live performance of their seminal single, “That’s The Joint.” The song has since been sampled for many classics, including Beastie Boys’ “Shake Your Rump,” EPMD’s “Da Joint,” and Naughty By Nature’s “Uptown Anthem.”

The Breaks by Kurtis Blow (1980)

Kurtis Blow’s “The Breaks” quickly captivated hip-hop fans with its relatable lyrics. With humorous rhymes like, “The IRS says they wanna chat/And you can’t explain why you claimed your cat,” Blow painted a vivid picture of some of the “tough breaks” ordinary people experience daily. The song was so popular, in fact, it became rap’s first gold-certified single merely two months after its release.

The Message by Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five (1982)

While “The Breaks” provided some comedic relief from the ills of the ‘hood, “The Message” addressed it head-on. Written by Furious Five member Melle Mel and Duke Bootee in response to the 1980 New York City transit strike, the track is often considered the first socio-political rap song. Each verse describes the inner-city poverty and violence they encountered daily. At the same time, it broke down barriers for others to follow suit, laying the foundation for MCs like Public Enemy’s Chuck D, KRS-One, and Ice Cube to deliver their own socially conscious messages.

Sucker MCs by Run-DMC (1983)

By 1983, hip-hop was finding its footing. Still, nobody was prepared for three kids from Hollis, Queens, to bust through the door the way Joseph “Run” Simmons, Darryl “DMC” McDaniels, and Jason “Jam Master Jay” Mizell did. With its abrasive tone and minimalist beat, “Sucker M.C.s”—produced by Russell Simmons and Larry Smith—showed off Run-DMC’s bravado and rhyming prowess. It simultaneously ushered in rap’s second generation and began Run-DMC’s meteoric rise to superstardom.

Egypt, Egypt by Egyptian Lover (1984)

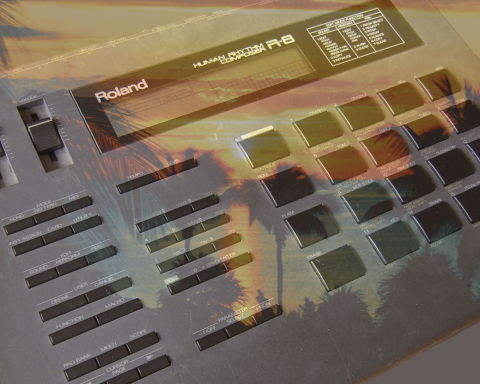

As a member of Uncle Jamm’s Army, Egyptian Lover was comfortable spinning records for hordes of people around Los Angeles. But with the release of “Egypt, Egypt,” the debonair DJ had the b-boys and b-girls salivating for more of his electro/hip-hop jambalayas. Created with the Roland TR-808, the track leaned on a riff from Afrika Bambaataa’s futuristic anthem, “Planet Rock.” It also helped introduce Egyptian Lover to a wider audience. To this day, “Egypt Egypt” remains the soundtrack to breakdancing battles worldwide

6 ’N The Mornin’ by Ice-T (1987)

Ice-T had lived a few lives before becoming a trailblazing rapper. Following a short military stint, he returned to Los Angeles with a plan to throw raucous parties like the ones his crew, Uncle Jamm’s Army, was hosting. But he took a sharp left after hearing Schoolly D’s “P.S.K. (What Does It Mean)” at a club one night. At that moment, he realized he could rap about the cold realities of growing up in the streets of Los Angeles—and unapologetically so. After adopting Schoolly D’s rhyming style, Ice-T wrote the lyrics to “6 in the Mornin‘” in his Hollywood apartment using a TR-808. The song was an undeniable hit and is widely considered one of the defining tracks of the era.

Microphone Fiend by Eric B & Rakim (1988)

“Microphone Fiend” was the second single from Eric B. & Rakim’s influential sophomore album, Follow the Leader. Against a heavy sample of the Average White Band’s 1975 hit, “School Boy Crush,” Rakim compared his propensity for “melting microphones” to those of an addict. With the swagger of a seasoned vet, he raps, “I get a craving like a fiend for nicotine/But I don’t need a cigarette, know what I mean?” The song effortlessly displayed Rakim’s innate ability to sprinkle intricate metaphors across everything he does—even when rapping about nothing more than a mic.

Straight Outta Compton by N.W.A (1988)

N.W.A hit the ground running in 1988 with “Straight Outta Compton.” Immediately, the explosive rap anthem had suburbanites clutching their proverbial pearls. With its raw, provocative depictions of gang life, it wasn’t long before the Parental Advisory stickers got slapped on every copy. Like Schoolly D’s “P.S.K. (What Does It Mean)” and Ice-T’s “6′ N The Mornin’,” the disruptive track gave Black youth, plagued by the ills of the street, a way to relate. It was platinum in June 2016, thanks to the success of the F. Gary Gray film of the same name.

Me Myself and I by De La Soul (1989)

Anchored by the production genius of Prince Paul, De La Soul—the Long Island trio comprised of Maseo, Trugoy the Dove, and Posdnuos—ushered in their self-styled D.A.I.S.Y. Age with 3 Feet High and Rising. The groundbreaking late ’80s release was an amalgamation of hip-hop, soul, funk, rock, and anything else the group could throw at it. “Me, Myself & I” reached No. 1 on the Billboard Hot R&B/Hip-Hop chart and went gold in June 1989, roughly two months after its release.

Fight The Power by Public Enemy (1989)

If De La Soul represented the peaceful side of late ’80s hip-hop, Public Enemy was the sound of war. Led by the revolutionary and inimitable voice of Chuck D, Public Enemy arrived on the scene in 1987. The group vocalized the ire of the millions of Black men and women who’d had it with the systemic racism littering the United States. In 1988, director Spike Lee commissioned the group to do a song for his new film, Do The Right Thing, which explored racial tensions in Brooklyn. The ensuing “Fight The Power” single addressed civil rights and a myriad of other important topics. It later appeared on Public Enemy’s third studio album, Fear of a Black Planet, in 1990.