When Roland released the polyphonic JX-8P in 1985, it was a time of change in the synthesizer industry. The JX-8P even had to contend with the popularity of its own JUNO-106. Modern synthesists are becoming fans too. Social media posts praise the instrument’s sound—clean and precise yet warm and rich. Now, with a ZEN-Core Model Expansion and the Boutique JX-08, it’s time to discuss the JX-8P again. So, let’s travel back to 1985 and find out what makes it so unique among the Roland polysynths.

FM Synthesis Arrives

In 1983, the first mass-market digital synthesizer arrived with the industry-disrupting DX7. Indeed, musicians couldn’t get enough of its crisp and glassy FM tones. Minimal design became the flavor of the moment. Synthesizer manufacturers ditched knobs and sliders for flush membrane buttons seemingly overnight.

Modern discourse likes to see the arrival of FM synthesis in black and white terms. Before it, there was analog, and after there was only digital. In actuality, the two synthesis forms happily co-existed for most of the ’80s. Analog still had its uses, often layered for the best of both worlds: crisp digital transients atop warm, lush pads.

To that end, the JX-8P reflects this mid-’80s sea change in both synthesizer sound and design. Yet it was an analog synthesizer, which remains a source of confusion among musicians. To achieve its FM-style vibe, the JX-8P used clever programming to create sounds associated with the DX7. The results were sounds like tuned percussion and even a surprising electric piano. Check out the woody Log Drum and Marimba patches for fun examples.

The JX-8P was no mere copycat, however. It could do lush pads, full brass stabs, and even a realistic piano sound. Indeed, the synth was the next step in the evolution of Roland’s analog synthesis.

"The JX-8P reflects the mid-'80s sea change in both sound and design. Yet it was an analog synthesizer."

The JX Connection

The JX-8P was a six-voice polyphonic synthesizer designed by the Roland Matsumoto R&D team as the successor to 1983’s JX-3P. Where the 3P of the original JX stood for Programmable, Preset, and Polyphonic, the 8P’s name was more obscure. But more on that later.

Like the original, the JX-8P had six voices with two oscillators per voice. Also, like the original, it sacrificed knobs and sliders for a sleek profile and used a single data slider to facilitate editing. Those wanting more control could opt for the PG-800 controller. The synth had a 61-note keyboard with velocity sensitivity and—importantly—aftertouch. It was also large, like an Oberheim, with an imposing, aircraft carrier-like presence. Its gray hue and tastefully-colored membrane buttons marked it as of its time but not garish.

Sonically, the instrument was bottomless. The JX-8P is most remembered for its pads and strings—and these it does beautifully. At the same time, it has a lot more up its synthesis sleeve than pretty sound beds. The JX-8P can do both acoustic and electric pianos and organs like nobody’s business. It even achieves FM-style percussion with its bells and marimbas. Let’s see how the JX-8P accomplishes all this.

"The JX-8P can do acoustic and electric pianos and organs like nobody’s business. It even achieves FM-style percussion with its bells and marimbas."

Digital Control

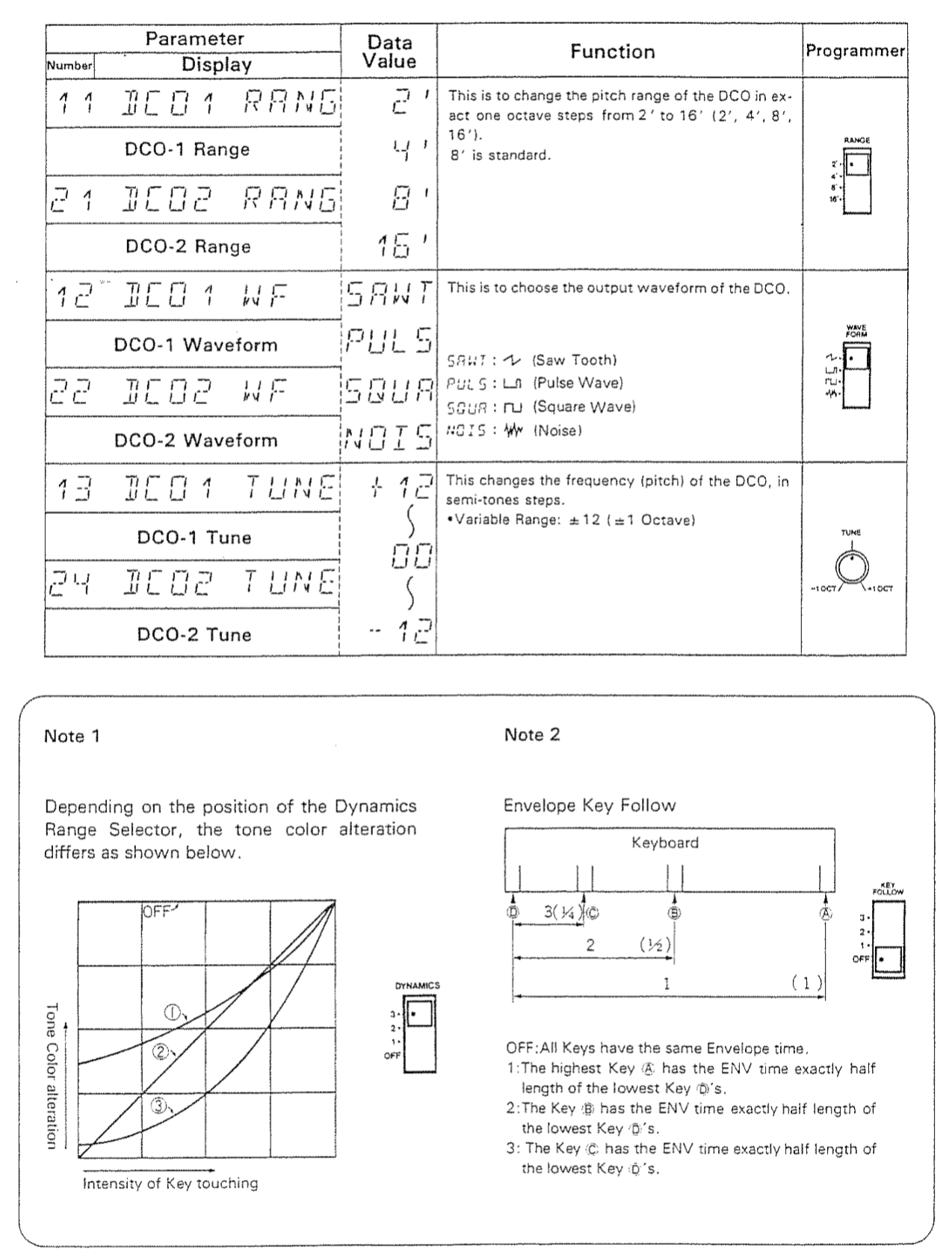

The JX-8P’s unique sound starts with the oscillators. As with many of Roland’s ’80s synths, the JX-8P had DCOs, or Digitally Controlled Oscillators. These were not digital oscillators, however. Rather, they were analog ones with digital influence over the pitch. The legendary Eric Persing was Roland’s Chief Sound Designer at the time. As one of two patch designers on the JX-8P, he explained the synth’s DCOs in the October 1986 issue of Keyboard. “The DCO puts out a raw square wave into an analog wave shaper circuit. This, in turn, converts the square wave into sawtooth and pulse waveforms,” Persing revealed. “Even though it is digitally controlled, a DCO creates sound through analog means.” Along with the sawtooth, square, and pulse waves, the two oscillators can also output noise.

The first key to the unique timbres of the JX-8P lies in DCO-2’s Cross Mod section. There are three cross-modulation options. Number one is a hard sync, forcing DCO-2 to restart its cycle in line with DCO-1’s. Although there’s no pulse width modulation per se, one can approximate the effect with oscillator sync. Cross Mod 3 is a form of frequency modulation, with DCO-2 as the carrier and DCO-1 as the modulator. The difference here is Cross Mod 3 supports key tracking, allowing for complex tones like bells that track the keyboard. Cross Mod 2 is a combination of sync and cross mod, allowing for even more tonal variation.

Filters

Roland is famous for its filters, offering a satisfying and chewy amount of resonance. The JX-8P had, much like the JUNOs, two filters, a highpass and a lowpass. It had a stepped highpass, offering three settings of increasing low-frequency shelving. The 24dB/octave lowpass filter was resonant but incapable of self-oscillation. Not a deal-breaker—users love the JX-8P more for beauty than raw power—but this could be a turn-off for some. The filter in the follow-up JX-10 did self-oscillate. This feature helped dispel the myth that it was two JX-8Ps jammed together.

Modulation Power

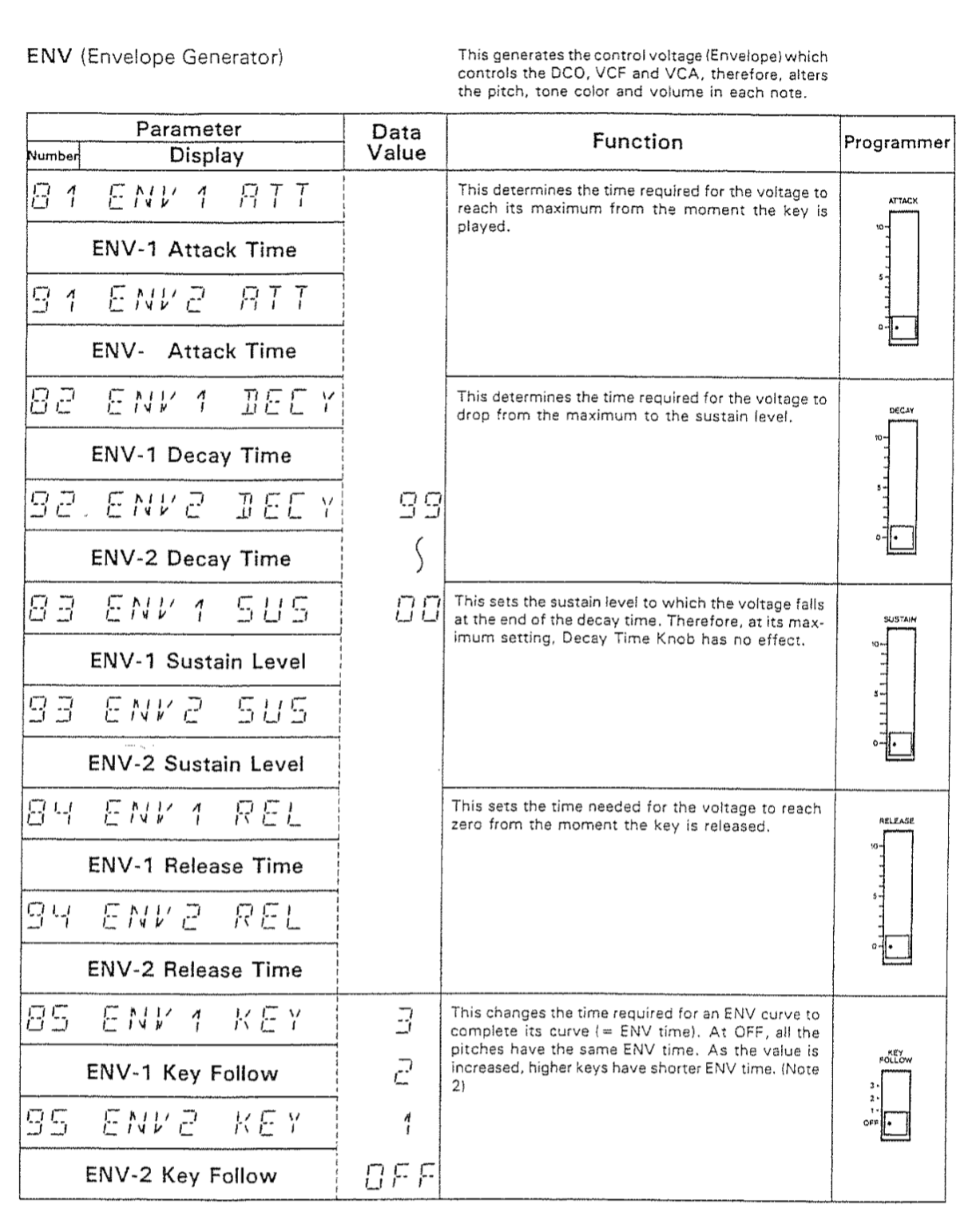

So far, we’ve seen how the dual DCOs and cross-modulation helped contribute to the JX-8P’s unique sound. The modulation section, namely the envelopes, also played a large part.

The original JX-8P brochures touted the fact that it had two envelope generators “for the first time in this price range.” Two ADSR envelopes offered more modulation opportunities, with possible destinations including the usual VCA and filter plus DCO pitch. Users could flip the polarity of each envelope from positive to negative, further opening up synthesis options.

By assigning an envelope to the DCO pitch and inverting it, players could create declinations in pitch, for example. Finally, envelopes had key follow. This meant the higher the notes played, the faster the shorter envelope became, creating a heightened sense of realism.

"By routing an ADSR to the volume of one of the DCOs, one could bring in overtones and harmonics based on pressure."

Many of the synthesis sections in the JX-8P offered a Dynamics setting of 0 to 3 which controlled how much velocity one applied. One could use this to increase the filter cutoff amount. Alternately, a player could also apply it to envelopes. This allowed controlling the dynamic range of envelope modulation in performance. By applying this to the pitch of one of the DCOs, one could add to a tone’s realism—for example, the attack of a brass patch.

Even without the fastest envelopes ever, a quick perusal of the presets reveals solid percussion sounds. In a Keyboard magazine programming guide, Persing noted the envelope speed as 0.1 seconds to two and a half minutes. There’s more to a good synth than the attack portion of its envelopes.

Velocity, Aftertouch, and Performance

As mentioned, the JX-8P had velocity sensitivity and aftertouch, one of only two keyboards in the same price range to feature the latter. This, plus its playability, contributed heavily to the JX-8P’s popularity with gigging musicians.

Synthesists could map Velocity to several destinations via the aforementioned Dynamics setting. We’ve already seen how one could use envelopes to affect pitch. Of course, it could also control volume—and not just overall volume, but the amplitude of individual oscillators. Yes, it had a voltage-controlled mixer. By routing an ADSR to the volume of one of the DCOs, one could bring in overtones and harmonics based on pressure. These were necessary elements for convincing acoustic recreations.

Aftertouch was global and applicable to overall volume, vibrato, and filter brilliance. There was a slider to set overall aftertouch sensitivity. This, used in combination with velocity, could create some very expressive sounds.

Patches And Presets

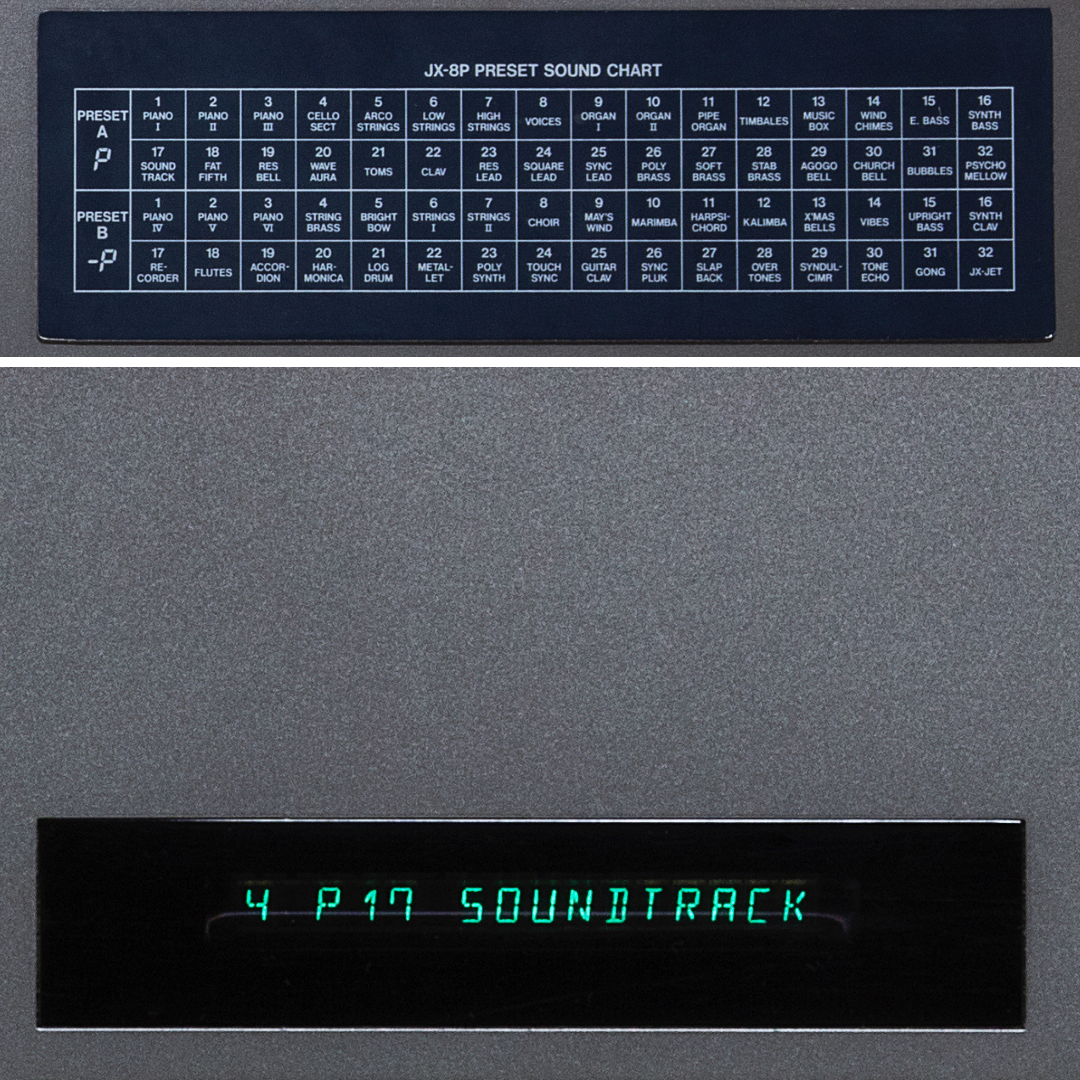

The JX-8P featured sounds designed by Eric Persing and Dan DeSouza. Alongside the MKS80, the instrument was one of Persing’s first jobs as Chief Sound Designer. It had all of his hallmarks: eminently usable and inspiring patches that showed off what the machine could do. As with later efforts like the D-50, some of the patches became famous in their own right. Even if you don’t know the patch name “Soundtrack,” you’ve certainly heard it in use. Angelo Badalamenti layered it (via an MKS70) with a D-550 string patch on the Twin Peaks soundtrack.

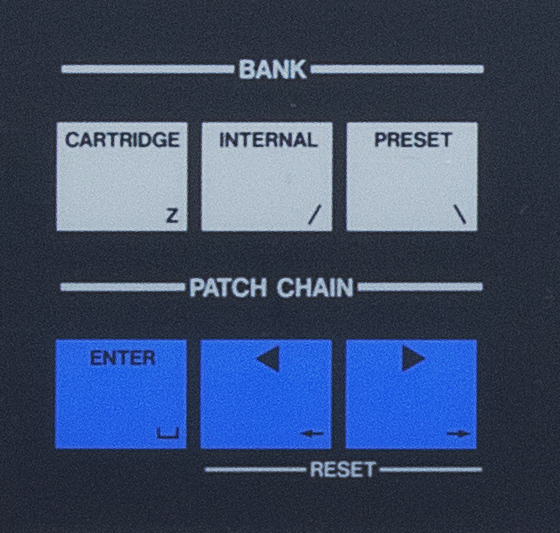

There were 64 preset slots, two banks of 32 each, that were expandable with the M16C memory card. Users could assign patches names, which was brand new at the time. Early models had the preset patch names printed on the buttons like the JX-3P but these disappeared in later builds.

The JX-8P also had a function called Patch Chain, aimed at live performers. It allowed them to assign their top eight patches to a special section for easy recall. Eight patches? That could very well be where the 8P in the synth’s name comes from.

"The JX-8P, with its slick DCOs and precise control options, fit synth pop perfectly."

JX Synth Pop

By the mid-80s, pop had moved on from the wild and woolly sound of the late ’70s to become sophisticated and sparkly. The JX-8P, with its slick DCOs and precise control options, fit synth pop perfectly. It was all over the charts in the second half of the decade, favored by artists like Depeche Mode, Go West, and The Cure. Jean Michel Jarre listed the JX-8P in the credits for his 1986 album, Rendez-Vouz. Vangelis had one. Devo used one. Trevor Horn loved his. The Human League. Stock Aitken Waterman. The list goes on.

Perhaps the most famous recorded use of the JX-8P appeared in 1986. “The Final Countdown,” the massive single from Europe, stormed the charts. This was, in no small part, thanks to its infectious opening synthesizer fanfare. Joey Tempest originally wrote the riff on another synth. Then, when it came time to record, he combined a JX-8P brass patch he programmed with a preset from another FM-based synth.

With performance-focused parameters and aftertouch-equipped keybed, the JX-8P was a hit with the era’s live acts. Kate Bush had one in her rig in 1987. Gary Numan even took a quintet of them on tour with him in 1985. “I’ve got five JX-8Ps,” Numan told International Musician in 1985. “Very soon we’ll be going on tour and I’m going to have two keyboard players each using two JX-8Ps. I’m going to keep one spare as well because you can never be too safe.”

Numan was a fan of both the synths sound and look. “I like the idea of that sort of uniformity on stage from an aesthetic point of view,” he said. “And from a sound point of view, it’s great because the JX-8Ps sound brilliant when MIDIed together.”

The JX-8P Legacy

The JX-8P was in production through the late ’80s, but its impact has been even longer-lasting. The instrument was reborn as the JX-10, a 12-voice polysynth based on the JX-8P engine and Roland’s last analog flagship. Later, it informed the MKS-70 and the rackmount JX-10. Plus, much as the JX-3P started life as a guitar synthesizer, the JX-8P passed on some of its DNA to a guitar-based application. The GR-77B, a bass guitar synthesizer, grew out of the 8P’s technology.

In more recent years, the JX-8P has been reborn in many digital forms. These include the ZEN-Core Model Expansion for instruments like the JUPITER-Xm and ZENOLOGY. The new versions feature the PG-800 functionality built-in plus expanded polyphony. The Boutique JX-08 has 20 notes of polyphony and effects as well as a sequencer. All that power comes in a box of much smaller dimensions.

Evolution Not Revolution

With its rich sound, MIDI SysEx, powerful unison mode, and that famous Roland chorus, the company delivered a classic. Capable of turning out gorgeous pads, brass, and FM-like percussion with equal aplomb, the JX-8P appealed to road dogs and studio rats alike. Moreover, with the JX-8P, Roland’s engineers pushed the evolution of synthesizers in the ’80s forward. The timeless elegance of the JX-8P continues to dazzle and inspire synth players today.