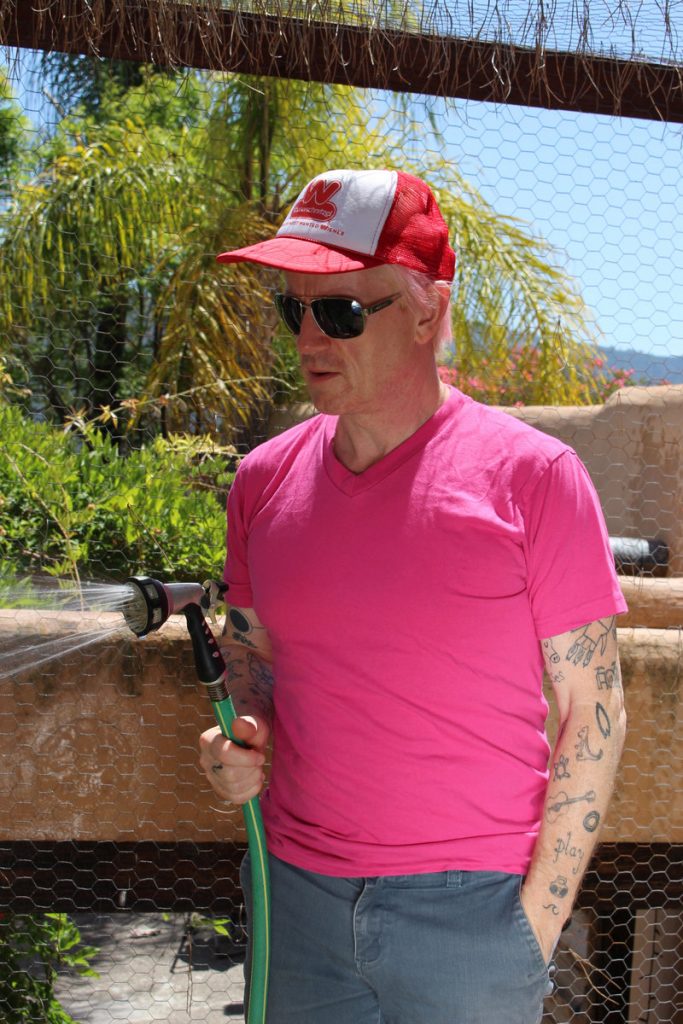

The madcap musical mind of Jacknife Lee is a wild and wonderful place. Producer, thinker, tinkerer, sampler—Lee has left his unique sonic stamp on albums by U2, REM, Weezer, Snow Patrol, Modest Mouse, Neil Diamond, Crystal Castles, and scores of others. Speaking from his home studio on St. Patrick’s Day, the Irish producer boasts a shock of bright red hair and arms covered with esoteric tattoos.

No Place for the Practical

Much like his approach to creating music, Lee is effortlessly iconoclastic. “Work isn’t supposed to be work,” he says, offering something like a credo. “I ended up doing this job accidentally. Then it became work, and I took it seriously.”

Lee’s embrace of a Zen-like beginner’s mind is a combination of preference and circumstance. It dates back to the beginning of his career. “My initial processes weren’t from a sensible or practical place. I started doing electronic music and my sampler had no capacity to store sounds. Every day I would start by resampling yesterday’s work.”

Colorful Collection

As he jumps around piles of eclectic gear, showing off everything from vintage keyboards to a piece he calls a “Walkman Mellotron,” Lee is every inch the eccentric dynamo. His journey from sample-focused bedroom producer to A-list collaborator is similarly unique. Following his experience in the agit-punk act Compulsion, Lee started remixing and began to attract more work. His unconventional approach became a calling card. “I was doing club mixes, R&B stuff, and hip-hop like TLC, Eminem, and Busta Rhymes.”

It was from this perspective that he began to, in his words, “re-engage with rock and roll.” Says Lee, “I took the things I learned from club mixes and started treating rock and roll in the same way.” It was a freeing experience. “Why is this sacrosanct? When you spend 20 grand recording an orchestra, why can’t you treat it the way you would a breakbeat?”

"When I started doing REM, I had to come clean and say I didn't know anything about technology, and I didn't really like it."

A Growing, Glowing Reputation

The music industry agreed. A remix from the film 28 Days Later led to an even higher tier of offers. “I got a Kasabian record, which they fired me on. I had no production experience,” he laughs. “From that, I got a U2 record, then Snow Patrol, and so on.”

As Lee’s acclaim and name recognition grew, so did the need to occasionally quantify his freewheeling studio style. “When I started doing REM, I had to come clean and say I didn’t know anything about technology, and I didn’t really like it.” With that legendary band, as with others, honesty worked in Lee’s favor. “They were intrigued.”

Even with a discography of commercial successes, Lee lets his instincts guide him. “I’ve returned to an amateur mentality, so I’m more playful.” Arena fillers like the Killers and up-and-comers alike find his attitude refreshing. “I’m going to present something that is a little less expected and only I can get it there. It’s not a conceit, I can only do that by maintaining an interest.”

"When you spend 20 grand recording an orchestra, why can't you treat it the way you would a breakbeat?"

How to Dismantle a Band

One act Lee worked extensively with is also a household name: U2. Lee’s methods gel well with the iconic quartet’s unique working style. “Their whole process is unusual,” Lee shares of his fellow countrymen. “It’s unlike any other band I’ve come across—they’re curious to a fault.”

Both adventurous and self-critical, the band trusts Lee’s vision and impressions of their material. “You’re expected to have an opinion with U2. They might jam for a while and I’ll say, ‘This four-bar section, there’s a song in here.’” Lee remains awed by U2’s lack of preciousness, especially for a group of its stature. “It’s complete curiosity and passion. Plus, lack of ego enough to drop an idea if it’s not good.”

Waltzing into the Club and Other Experiments

Lee possesses myriad ways to push artists out of their comfort zones. “In remixing, if someone gives me a song in 3/4 and they want a club track, I’m thinking, ‘Well, waltz hasn’t been big since the 1700s. I’m going to have to make it 4/4.’” In general, he finds pliability makes for the best results. “The way something is doesn’t mean that’s the way it is. It just means that’s the way it is this moment.”

Take another Lee production, Weezer’s hit “Pork and Beans,” with its wildly contrasting verse and chorus sections. “Technically, it was a really bizarre process I tried. There was a lathe next door to the studio, so everybody recorded the parts and we pressed them onto vinyl.” The experimentation didn’t end there. “We sampled from the vinyl, and everyone got behind a keyboard to play loops of their parts by pressing a key.”

"I’m intrigued by things interrupting each other without advance warning—like losing the concept of a drum fill."

The result is an off-kilter push into the song’s crushing chorus. “It’s a different tempo than the verse. They went with it, and it works,” he says. “I’m intrigued by things interrupting each other without advance warning—like losing the concept of a drum fill.”

Random Access—No Memory

Lee is a collector and gear enthusiast—the odder the better. Just don’t call him a purist or tech head. “I used to think it was a fault that I couldn’t remember anything. Now I realize it’s a gift.”

Furthermore, he won’t allow yesterday’s work to dictate tomorrow’s, even if it makes studio life more challenging. “I never save presets, and I don’t have a go-to vocal chain I install every day,” Lee says. This preference extends to his taste in instruments. “I like not having the capacity for saving. It’s a risk you might not get there again, but you might get somewhere else.”

"I like not having the capacity for saving. It's a risk you might not get there again, but you might get somewhere else."

In a studio packed with equipment spanning many brands and eras, Roland factors heavily, both in hardware and software forms. “I’ve got a JUNO-106 over there, and the Roland Cloud JUNO-60 plug-in is amazing. I’ve also got the MKS-80 Super Jupiter and a JV-1080.” Amid vintage Roland JC-120s and drum machines, Lee notes a particular box and its influence on a famous client. “I used the TR-8 all over U2’s last record, so they went and bought one. Now I’ve got the TR-8S.”

Orphaned Tracks to Acclaimed Release

His latest solo record, The Jacknife Lee, is a wide-ranging batch of tunes created with handpicked artists from around the globe. The list of co-conspirators includes Genesis Owusu, Aloe Blacc, Beth Ditto, and others. “These started as tracks no one wanted,” Lee shares in self-effacing fashion. “I’d send them to somebody I’m a fan of, like Sneaks or Muthoni Drummer Queen.”

The result is a kaleidoscopic collection. Pitchfork calls it “an electronic melange featuring a surprising roster of guests.” From dreamy opener “Flutter” to the synth tapestry of “Firewalls,” if the album has a through line it’s the futuristic world rhythms.

The Unexpected Benefits of Imposed Isolation

To an artist like Lee, even the challenges of COVID-19 provided creative fuel. “I don’t know if it’s Zoom, but people are more open. Getting out of the way of the social interactions enabled them to be a bit bolder with what they’re interested in.”

In addition to Modest Mouse, he’s been helming releases by the Regrettes, post-punkers A Certain Ratio, Malian singer Rokia Koné, and James. “I’m working seven days a week. I don’t like doing anything else,” he admits.

"Getting out of the way of social interactions enabled people to be a bit bolder with what they're interested in."

Future Tense

Lee’s intrinsic love of music is what pushes him to continue challenging the status quo. Even when shooting for accessibility, he strives to make records that provoke the listener. “Are the records I’m making records I would drive 40 minutes and pay 30 bucks to buy on vinyl? Why would I commit four months of my time to work on a record that I didn’t want to buy?”

One release of which he’s particularly proud is Open Mike Eagle’s Anime, Trauma and Divorce. “I love him, and I didn’t know I could mix a hip-hop record that could impress people like Madlib.”

Ultimately, Lee seeks out projects that keep him excited—about both the sound and the creative process that goes into capturing it. “I’m interested in the idea and the feeling,” he explains. “No one’s goal is to be boring, but people forget that and get comfortable. If you’re not a bit frightened, then it’s boring.”