There’s no doubt the rise of the “lo-fi beats to…” trend has strong ties to Japan. The YouTube channels and Spotify playlists with their Studio Ghibli-esque aesthetics exemplify this connection. Japan maintains a strong association with the internet phenomenon’s origin story. Fans of the sound from decades back might have an opinion about its popularity, many feeling that the widespread appeal has diluted and reduced something that had such strong musicality at its core. However, one can also argue that what it has done is provide an entry point for a younger generation. These new recruits are getting a taste of a style that contains untold riches—if they dare to dig a little deeper.

A Sound is Born: Jun Seba and the Early Days

Jun Seba aka Nujabes is a producer and beatmaker extraordinaire. He is often cited (with J-Dilla) as a godfather of the lo-fi movement. Seba’s contributions to the Japanese beat scene, through his label Hydeout Productions and the Shibuya icon that was Guiness Records remain unmatched.

Seba’s soundtrack for the 2004 Shinichiro Watanabe series Samurai Champloo is the link between atmospheric flips of jazz and soul samples with Japanese anime. Indeed, it’s revered by the new generation of music fans who are discovering his timeless music for the very first time.

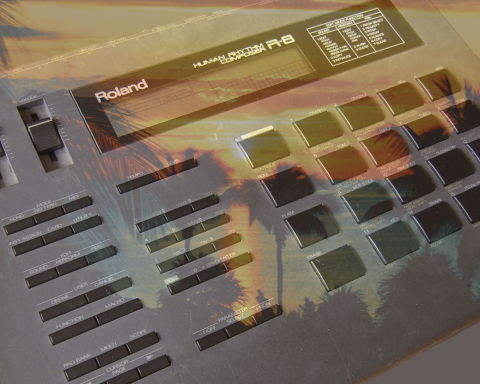

Still, Nujabes is but one name in a long list of pioneers who’ve contributed to the layered history of Japanese beatmaking. In this history, the perfect storm of unlimited source material exists in the record stores of Japan’s urban centers. In addition, beatmakers around the world use hardware birthed in Japan—like the SP-404—to create these beats. This all adds up to a unique expression with a Japanese heart. Starting in the late ’80s, a new generation of bedroom producers, DJs, and future cultural icons began to unleash sample-based hip-hop on dancefloors and the world.

"Jun Seba's soundtrack for the 2004 Shinichiro Watanabe series Samurai Champloo is the link between atmospheric flips of jazz and soul samples."

Japan Arrives: Major Force, DJ Krush, and More

Founded in the late 1980s, Major Force marks the beginning of, not just Japanese hip-hop, but Japanese dance culture in general. Helmed by cultural visionary Hiroshi Fujiwawa alongside Ken Takagi, Masayuki Kudo, Toshio Nakanishi, and Gota Yashiki, Major Force released a series of 12-inches with a uniquely Japanese take on the upfront hip-hop and club music of New York and London. These records would in turn make their way out of Japan and to the record stores of the very cities that inspired Major Force. They also won over key tastemakers along the way.

One of those was a fresh-faced record store employee called James Lavelle who worked at Honest Jon’s on Portobello Road. Inspired by the Major Force label, Lavelle would go on to establish the legendary ’90s record label Mo Wax. A compilation of Japanese hip-hop followed in 1993. With the following year came DJ Krush’s seminal Strictly Turntablized. The album blew minds globally and marked Japan’s arrival on the global stage as a beatmaking force.

"Major Force released a series of 12-inches with a uniquely Japanese take on the upfront hip-hop and club music of New York and London."

Forging an Identity: FILE, Jazzy Sport, and Beyond

By the mid-’90s, import sections of record bins worldwide began to feature a handful of other Japanese names. All were helping to forge a Japanese identity through sample-based instrumental beats. These ranged from the bossa nova-fuelled Future Listening! by ex-Deee-Lite DJ Towa Tei to the thick, moody beats of Indopepsychics and the cosmic experimentation of Riow Arai. The latter was an in-house composer at video game company Squaresoft by day. After hours, and across a multitude of subgenres, he was pushing the boundaries of Japanese electronic music.

A handful of names got out to the world via compilation licensing and import record distribution channels. Still, what the world was missing was a whole other universe of Japanese DJs, rappers, and beatmakers. These artists took the boom-bap influences of the East Coast and shaped the domestic scene and the future of Japanese beats. One of the iconic Japanese hip-hop labels, FILE Records was a Tokyo-based imprint. They were responsible for releases by Scha Dara Parr, Rhymester, and Microphone Pager (featuring the King of Diggin’ DJ Muro). One individual to play a key role at FILE Records was Taro Kesen, founder of the Jazzy Sport record store. He discusses the influences of this era as hip-hop culture exploded in Japan.

“For me, it began when I was 14 years old and I was really into Malcolm McLaren’s album Duck Rock. Back then, our access to hip-hop was through Japanese magazines and FM stations which played a mix of new wave and underground music. Then it was all about Major Force. It was very important to me to see local Japanese artists reacting to hip-hop and DJ culture like I was. I think many kids my age were influenced by Major Force. Then came acts like Rhymester as well as other artists on FILE Records. I got to know FILE Records through Major Force because FILE distributed their records. I think FILE was an important label for music lovers like me back then as they signed and released all kinds of underground Japanese music, not just hip-hop.”

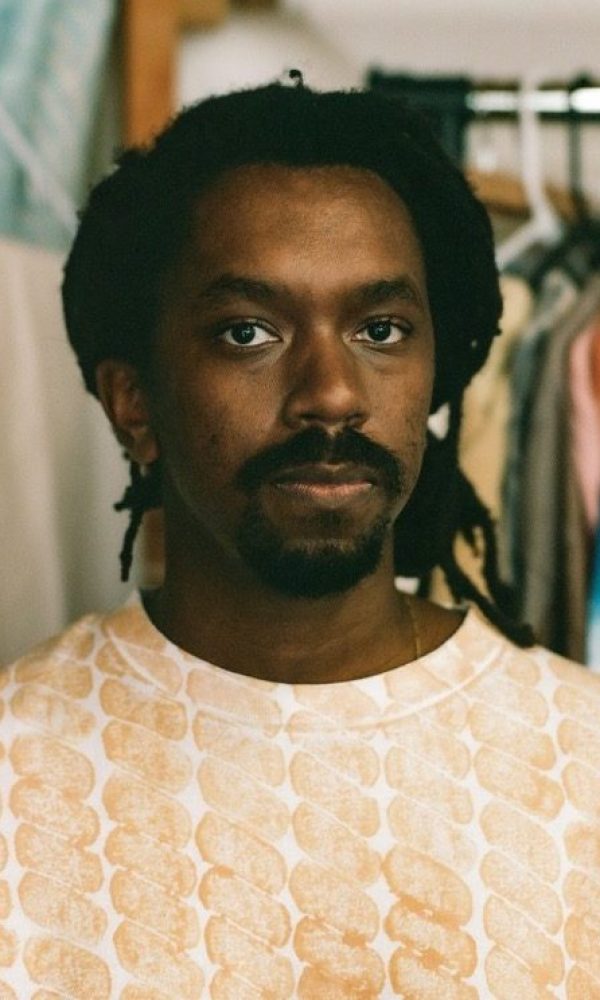

TARO KESEN

A Heady Mix of Sounds

In the early ’90s, Taro moved to London to study English and to soak up the music and culture exploding in London. He spent days in record stores like Blackmarket Records, Bluebird, and Honest Jon’s and evenings at club nights. Some included Rage at Heaven, High on Hope at Dingwalls, funk, soul and rare groove nights at the Fridge, and the Soul II Soul sound system. In between, he took in as much pirate radio as he could fill his cup with. This heady mix sowed the seeds for what would, a decade later, become one of Japan’s most iconic record stores and labels.

When Kesen returned to Japan in 1995 he joined FILE Records, eventually working his way to the A&R department. There he received a demo tape from a group that called themselves GAGLE. It pushed him and partner Masaya Fantasista to start a label and store of their own. Jazzy Sport was born in 2003. It went on to mark the beginnings of a new chapter in Japanese underground music.

"Jazzy Sport, founded in 2003, was the label that would go on to mark the beginnings of a new chapter in Japanese underground music."

“We were inspired by independent labels like Laws of Motion, Main Squeeze, Fondle ‘Em, and Stones Throw. They were all putting out quality music and vinyl all the time. We were also into this formula of exploring the relationship between music and sports—which is a big part of the label’s identity. But most of all, we just liked the idea of having freedom and not having a boss! We could release what we liked.”

TARO KESEN

Cratediggers Delight

What came next were incredible debuts from DJ Mitsu The Beats, Grooveman Spot, and the name that started it all, GAGLE. Plus, some seriously earth-shattering, alternate-dimension unlocking remixes. The Jazzy Sport logo soon became synonymous with a new Japanese sound. This aesthetic blurred the rhythmic lines between hip-hop and house. It was imbued with the musicality of decades of African-American musical tradition found in Shibuya’s record stores. With support from DJs Gilles Peterson, Benji B, Daniel Best, and other European tastemakers, the Jazzy Sport label charmed its way around the world. The record store back in Tokyo served as a beacon for traveling music heads seeking to fill their suitcases with a fresh Japanese take on beats.

The Legend of Budamunk

One of these individuals that heard about the legacy of Jazzy Sport was a beatmaker by the name of Budamunk. Regarded as one of Japan’s consummate beatmakers, Tomonobu Kanno aka Budamunk was born in Japan but moved to Los Angeles in 1996 at the age of 16. It was in this new environment that he got properly hooked on hip-hop. In particular, young Kanno loved the music of A Tribe Called Quest, Slum Village, and the production of JayDee and Erick Sermon.

Soon, he fell into a community of heads gravitating more towards beats than rhymes. On the LACC campus in East Hollywood, he’d meet an MC by the name of Joe Styles. Like him, Styles was also getting serious about unlocking the power of a machine that seemed to be the source of the beats that they loved: the MPC. Together with OYG, they formed a crew called the Keentokers. It was about this time that these early forays got serious. Budamunk recalls:

“I didn’t really know how to use the MPC and so I learned a lot from Joe Styles. He didn’t know how to fully use it either, but he could make a beat out of it. He would make a sick beat and I would just watch and learn. Another member of our crew was a guy called LAID LAW who was the brother of Chali 2na. He was close friends with DJ Dez from Slum Village. So LAID LAW and Joe would go to this house, see him work, and learn from him. Then they would show me later. That’s how we learned the craft back then.”

BUDAMUNK

Budamunk got his technique down fast and soon developed a name for himself in the Los Angeles underground as a formidable beatmaker. In 2005, he won the first-ever Scratch Academy MPC Tournament, run at the time by Jam Master Jay. Yet just as his name was getting etched into the LA underground scene, his US Visa ran out. This landed him back in Tokyo with no name and no connections. It was Jazzy Sport’s exploding reputation in the global underground that gave him an objective upon his return to Japan.

“I had been away for ten years and had absolutely no knowledge of the local hip-hop scene. But I had heard of the name Jazzy Sport because everyone was talking about it back in Los Angeles before I left. So I made it my number one mission to link with them as soon as I returned. When I returned, I found that they were massively popular. Their events would always be packed and the atmosphere at those events was incredible. They were the guys that were making beats even before there was a beat scene so I think that Jazzy Sport can be credited with starting a new genre of hip-hop in Japan. For me, that’s the real start of the Japanese beat scene.”

BUDAMUNK

Heart of the Scene

At the heart of the scene was the Jazzy Sport record store. Today, the store is in the more laid-back neighborhood of Gohonji in Tokyo’s Meguro Ward (along with an outpost in Shimokitazawa). Back then, however, it existed in the center of the heaviest density of record stores in the world: Shibuya’s Udagawacho. There was a bar and a never-ending stream of local heads and international visitors passing through. Jazzy Sport amassed a reputation as one of the vibiest spots for underground music.

It was in this environment that local artists formed new bonds and hatched projects. In 2008, Budamunk marked the beginning of a phenomenal output for Jazzy Sport. By that point, now a firm part of this growing local scene, he linked with Japanese artists like Issugi and 5lack to forge new musical partnerships. These helped shape the future of the Japanese beat scene, birthing untold classics along the way.

The Osaka Sound

Jazzy Sport was very much the center of Tokyo’s growing community of homegrown beatmakers in the mid-2000s. At the same time, Osaka was developing its own scene. Its pulsating heart was a curated “select shop” called LOSER helmed by artist, DJ, and cultural curator Mayumi Takada. Also known as mayumikiller, Takada took over LOSER in 2006. This was a time when a new crop of producers and beatmakers were emerging out of Los Angeles with a singular sound.

LOSER became the place for carefully-selected records, cassettes, used clothing, and myriad other music-related treasures. It all showcased the exploding creativity of the emerging LA beat scene to a local Japanese audience. For Takada, it was Flying Lotus’s debut, 1983, and his first Japanese tour that marked the beginning of an exciting era for Japan’s own beat scene.

“It was such a huge impact on the scene when Flying Lotus played live in Osaka for the first time. There was already a strong fanbase of Japanese listeners for the more electronic end of instrumental hip-hop, artists like Prefuse 73, Machinedrum, and of course J-Dilla. But what Flying Lotus was doing was so different and Japanese people really paid attention to it. That first Flying Lotus show and then the first Brainfeeder showcase with artists like Ras G, Gaslamp Killer, Jon Wayne, and Teebs. They all changed the fundamentals of the scene in Japan. I think we can say that what we call the current ‘Japanese beat scene’ really evolved from the impact that these LA artists had.”

MAYUMIKILLER

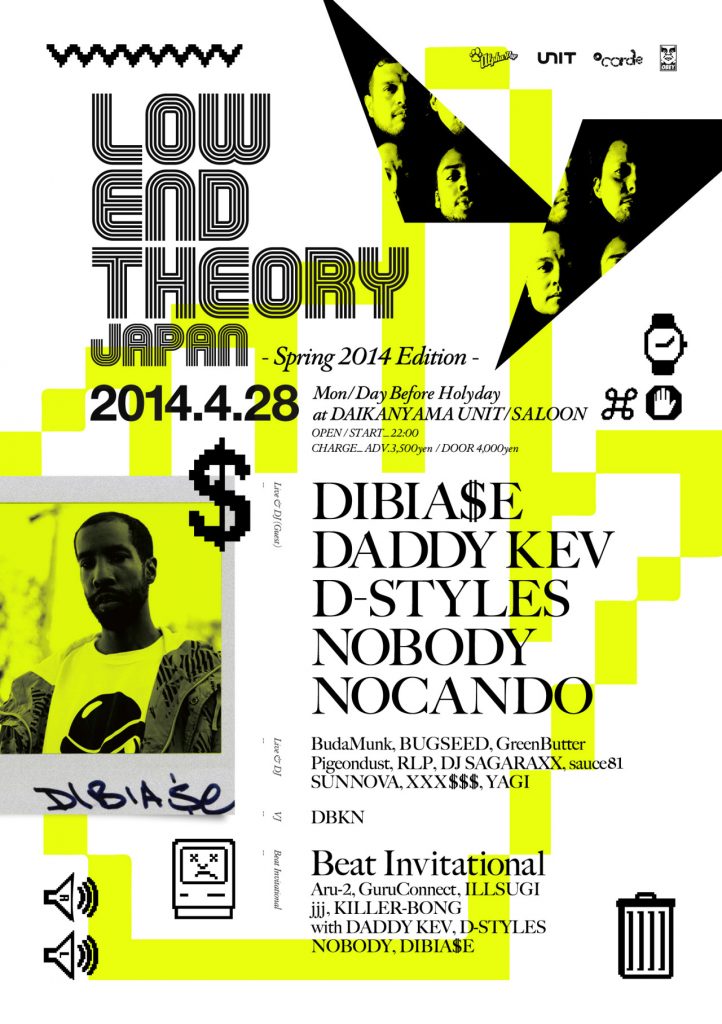

Low End Theory: A New Movement

The epicenter of this exploding creativity coming out of Los Angeles was the weekly club night, Low End Theory. There, founder and Alpha Pup Records label head Daddy Kev—alongside residents Nobody and D-Style—curated a phenomenal selection of artists pushing this sound into outer dimensions. Japanese audiences soon got a regular taste of this exploding creativity. “Low End Theory Japan” tours would happen almost quarterly from 2008 until 2015. Responsible for organizing the tours was Japanese music journalist and founder of dublab.jp, Masaaki Hara. He remembers the feeling of witnessing something completely fresh.

“I saw Low End Theory for the first time in 2008 in Los Angeles when I was writing a piece for a magazine. Flying Lotus was performing live and it was right before the debut for Warp when he wasn’t very known but was already popular in LA. They were having this Beat Invitational where they competed by playing their beats. I remember being impressed by the fact that it was just beats and the crowd was going absolutely wild. I interviewed Daddy Kev and he told me that since Low End Theory took off people started to focus more on the beatmaker unlike before. And that there are a lot of young artists coming into the scene.”

MASAAKI HARA

One of those young artists was Mtendere Mandowa aka Brainfeeder recording artist Teebs who would get the opportunity to be a part of the Low End Theory tours that Hara put together in Japan with co-collaborator Hashim Bharoocha. He recalls the feeling of taking this new sound, forged in Los Angeles, to Japan for the first time.

“It was mind-blowing. Honestly, I find it hard to put into words. Really life-changing. We were all there to represent the Low End Theory sound, and it was crazy to see how much everyone in Japan was truly and deeply interested in what we were doing. Low End Theory had been going for a couple of years, but it was still pretty underground. Just a few people cramming into that little space back in LA. But then to go to Japan and see big billboards with our names on them. Knowing we had sold out these big venues. It was just so incredible to see how far that sound had spread.”

TEEBS

Once inside, the atmosphere at these performances in clubs like Tokyo’s legendary UNIT in Daikanyama and WWW in Shibuya was electric. It was like nothing many of the LA artists had experienced before. An energetic Japanese audience soaking up this cutting-edge sound. Teebs remembers clearly his first-ever show.

“I was pretty new to these big venues and so it was shocking to see them packed out. Ras G was going back to back with Daddy Kev, and it was this wild explosion of energy from the audience. I remember Nocando turning towards me, and I was still pretty young, and he was looking at me saying with his eyes. ‘You’re next…” And I’m like this little kid. It was that first moment in your life when you’re at the real pinnacle of something crazy happening and starting to understand how nuts it is. I was about to put out my first record, so I was pretty much ready with my favorite music I’d ever made. Ras G and I were both running 404s that night, and even I was shocked pressing those buttons for the first time and hearing how good the music sounded loud. It was wild. Really, really wild.”

TEEBS

The Eureka Moment

But it wasn’t solely in the big venues like UNIT where these Low End Theory showcases took place. Each of the local hubs also played host to various in-stores and happenings. LOSER in Osaka served as an important host for live performances from many of the scene’s greatest. These included Daedelus, Teebs, Ras G, Mndsgn, Machinedrum, and others. Virtually all of Japan’s beatmakers—past, present, and future—were at these seminal Low End Theory club events and smaller shows. What they paid the most attention to was the hardware many of these LA artists used in their sets. Mayumi recalls the eureka moment locals had seeing their favorite producers making colossal, pulsating beats on all-new, portable Japanese samplers.

“What stood out was the machines they were using. In the early 2000s, it was the MPC that beatmakers were using. But from 2009-2010 on, it was the SP-404. For many Low End Theory artists, they wanted to play overseas with the most simple setup. The SP-404 was very portable to take on tour to Europe or Japan. Especially for artists like Ras G, who was always touring and almost never in LA, the SP-404 was compact, battery-powered, and tough. When you would be at the Low End Theory live shows, the bass sounds you could get from the SP-404 stood out. So when Japanese people saw artists that they really respect like Ras G and Teebs were using the SP-404, it left a lasting impression on everyone.”

MAYUMIKILLER

“I remember kids getting closer after the show looking at the SP-404 saying, ‘What are you using? I didn’t even see any wires coming out of it.’ It was just RCAs. And I would show them how simple it was. For touring, it was perfect. It was tiny—you could store it anywhere. You go to a different country; you don’t have to start worrying about whether or not the power will fry it. You just need six AA batteries, and you got those around the world. It was universal.”

TEEBS

Connections Made in the Underground

For many of the artists coming to Japan during this golden era, it wasn’t just about showcasing a sound that they had forged in their home cities. They were able to get a taste of what was happening in Japan’s underground at the same time. For Teebs, he recalls the feeling of seeing Japanese artists like Daisuke Tanabe.

“Connecting through touring was what made it real for me. Like, we would be playing somewhere and you would meet certain people and someone would say, ‘Oh, you have to check so and so.’ Then we’d see someone like Daisuke play and hear how crazy he is. It was just like, ‘Alright, you’re one of us. I can already tell.’ You know you’re going to be cool forever because this person’s music and their ethos is exactly on it. And if he was in LA, he would have been flying to Japan to play tonight. You know what I mean?”

TEEBS

For many of the local beatmakers and producers, there were additional benefits. The regularity of these tours, coupled with the fact that so many producers would extend their stays with multiple shows, created an environment where ideas and influences got exchanged outside the four walls of a club. For Daisuke, the curiosity and mutual respect were reciprocated between both sides, forging lifelong connections.

“When I got invited to perform at the Low End Theory events in Japan, it weirdly felt like I was invited to visit them in Los Angeles and not the other way around. They weren’t the guests in that event that night. It felt more like we were. At the time I was hugely inspired by Flying Lotus, Gaslamp Killer, and Tokimonsta but none more so than Teebs. The music and art he creates has this consistent character to it, and reflected the essence of who Teebs was. From his works and his performance I learned the beauty of expressing oneself, honestly.”

DAISUKE TANABE

The Influence of Ras G

Each Low End artist was revered by local beatmakers and helped influence the community in their own way. But one artist who left a phenomenal impact was Ras G. His music, energy, presence, and skill would consistently move Japanese audiences. This was true on every tour he did up until he passed in 2019. Known as one of the greatest to utilize the SP-404 in studio and live environments, Ras G influenced a generation of beatmakers. These included future Roland engineer, Takeo Shirato. He recalls hearing how the SP-404 was shaping the community in Los Angeles and seeing this firsthand on the subsequent tours.

“I think it was around 2010 when I first became aware of this new community around the SP-404. Japanese music magazines such as remix and ele-King featured Low End Theory and Brainfeeder. Through them, I learned about the existence of artists like Samiyam, Teebs, Ras G, and Tokimonsta who were using the SP-404. At that time, Low End Theory toured Japan about once every year, and I went to see their performances. I had seen Ras G several times, but the show that left the biggest impression on me was at UNIT in Daikanyama around 2012. It was a divine performance. It was a psychedelic and spacey evening, with bass and beats synchronized with the rhythms of the universe, interspersed with samples of Sun Ra. It may be because I love Sun Ra, but it felt special.”

TAKEO SHIRATO

A Future Engineer’s Story

Shirato spent most of the 2000s with his head deep in record stores chasing samples. He was heavily inspired by local DJs spinning a multitude of genres in his home base of Mito City, Ibaraki Prefecture. Record labels like Stones Throw and the expert curatorial finesse of head Eothen Alapatt aka Egon Takeo also made an impact. Learning that two favorites, Madvillain’s Madvilliany and J-Dilla’s Donuts, were largely built on the SP-303, Shirato fell deep into SP culture. In 2017, he joined the Roland team. Two years later he joined the team that would develop the SP-404MKII. The communities online and in real life helped shape the new instrument’s development.

The 2010s and Japanese Beats Go Further Worldwide

In the 2010s, a new generation of Japanese beatmakers strengthened the reputation of their scene around the world. Artists like Yosi Horikawa and Daisuke Tanabe forged distinctive grooves with a distinctively Japanese sensibility. They mesmerized audiences around the world. Back home in Tokyo, hubs like Solfa Nakameguro and nights like 90 BPM Takeover took the Low End Theory spirit and further shaped the beat scene. Along the way, they showcased the talents of local producers like Bugseed, Submerse, and Fumitake Tamura. At the the same time, Japan’s SP-404 community was growing. A new generation of beatmakers and enthusiasts were helping to grow the scene in Tokyo, Kyoto, Osaka, and beyond.

"Throughout the 2010s, a new generation of Japanese beatmakers strengthened the reputation of their beat scene around the world."

The Now Generation

Reo Matsumoto is a multi-talented musician, beatmaker, and beatboxer. Arriving back in Japan in 2019 after more than a decade of touring the world, he’s something of a dynamo. After learning how to beatbox at the age of seventeen, Reo went on to represent Japan at the World Beatbox Championships. He soon got a taste for travel and spent more than a decade touring the world. Matsumoto integrated himself into local music scenes in London, New York, Melbourne, and many cities in between. Inspired by beatmakers like Gaslamp Killer and Dibia$e, Matsumoto eventually got an SP-404. Using the internet as his platform, started to build a name for himself in the global SP-404 community.

Since returning to Japan, he’s been active as part of the local scene, especially through Goodfellas Tokyo. The brand is designed to highlight the next generation of Japanese beatmakers through a series of club nights and online showcases.

“We started Goodfellas for those of us out there who are making beats like us. It’s not DJs at this event, it’s all about the beatmakers. The idea is that we bring together people from a whole range of wider culture. Videographers, designers, dancers—all coming together to see what will happen. But at the heart, it’s about the beatmakers making the night. For me, Tokyo is a great extension of the SP-404 global community. I come from a background as a musician, and I’ve always loved to jam and improvise a lot. Traveling, meeting people, jamming together. That’s me. So, the fact that I can go outside with the SP-404 and jam with other musicians, with other instruments, or even with other SPs, this is all perfect for me.”

REO MATSUMOTO

Pushing Beats Forward

Across Japan, the spirit of pushing the beat scene forward continues. It ranges from groundbreaking nights at Solfa Nakameguro and local crew nights like Table Beats in Kyoto to LOSER in Osaka and Goodfellas Tokyo. Established names still hold the torch, but there is a constant stream of new producers busting through with serious heat. Their ranks include cell d break, Tajimahal, Green Assasin Dollar, Phennel Koliander, labels like Hermit City Recordings, and many others. Whatever the case, there’s no doubt that Japanese unique beatmaking lexicon will do nothing but expand. As it does, the SP-404 will continue to help shape the future of one of the most dynamic and exciting musical communities in the world.