Few sound designers inspire the kind of fan recognition Eric Persing does. Based in Los Angeles, Persing is the founder and Creative Director of Spectrasonics. Prior to that, the multi-talented synthesist worked for Roland as Chief Sound Designer. Between 1984 and 2004, he contributed to many influential synthesizers and modules including the D-50, JV-1080, and others. Of his many projects, 1991’s JD-800 holds a special place in Persing’s heart. A striking instrument, it retains a loyal user base and appears on countless recordings. The JD-800’s lead sound designer gives us the scoop on this classic synth.

A Special Connection

What was your connection to the Roland JD-800?

More than any other project I worked on for Roland, I think of the JD-800 as my baby. I was proud that everything came together on the JD-800, and it was the evolution of the D-50. It’s funny because people didn’t think of the D-50 as having limitations because it was so successful and made such a big impact. However, there were things we thought could have been better. One was the response. When you played the D-50, the main processor was doing everything, so it wasn’t the tightest feel. It was hard to get tight chords out of it—there was delay. It was great for pads, but not so great for really tight kinds of things.

"The idea was always that it would have a stealth bomber kind of look. Plus, the panel had a

strong identity."

What did you accomplish with the JD-800 in response to that?

One of my favorite things about the JD-800 was that it had separate processors for the keyboard and sound engine. Plus, it had separate chips for the filters and effects. It was more of a “discrete design” which you didn’t see often in digital instruments. This made a difference in performance.

Pretty much every synth after the JD-800 went to more of a single chip design, but there’s something about that kind of separation. It made it a professional instrument. When you play it, there’s almost no delay at all between the keyboard and the sound engine. It feels more like playing an analog synth where you don’t have that microprocessor scanning thing. Integrating that into the body and concept of the instrument was exciting.

Southern California Sound Design

Tell us a bit about the development team behind the JD-800.

Roland R&D Los Angeles was a short-lived office that was a part of Roland, Japan, based in Culver City. We were a really small group: Chris Meyer, Mark Tsuruta, Bob Daspit, and myself. The idea was that Roland Japan began to send engineers to Roland R&D Los Angeles. We could get into sound and product development without going to Japan. There was a lot of room for the engineers to refine how we did sound design, sampling, and synthesis. As a result, the JD-800 was the first product designed half in Japan and half in Los Angeles.

Can you describe your overall role in the project?

I’ve always felt a strong connection to the JD-800. It was a big deal for me and those of us who worked on it because it was the first project that we did at Roland R&D Los Angeles. This was a new sort of relationship and a wonderful opportunity for me because I got to have a lot of input. I got to do all the waveforms and almost all the patches. It was the most involved I’d been up to that point.

"I've always felt a strong connection to the JD-800. It was a big deal for those of us that worked on it."

A New Approach

What do you think made the JD-800 so unique?

The waveforms are very clear, and it’s a pro instrument in every respect. It was a successful instrument with professionals. Intentionally, we didn’t have traditional instrument sounds or that kind of thing. We used all the memory, which was a total of four megabytes. All of that was for waveforms, except we added a piano.

There were no string waveforms, saxophones, or brass. This was at the time of the popularity of workstations, and the market wanted a keyboard to do everything. The JD-800 was a bold statement because it was like, “This is a synthesizer, and it makes synthesizer sounds.”

You’re recognized as one of the world’s most preeminent synth sound designers. Yet a big part of the JD-800 story was its physical and mechanical design.

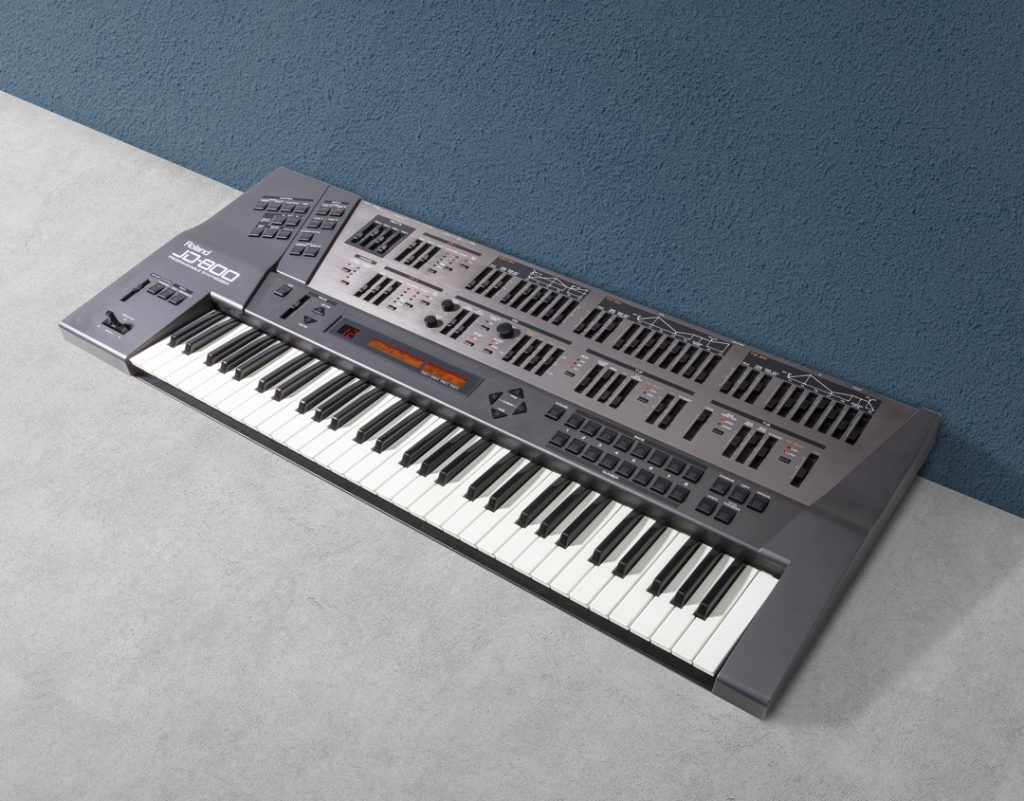

The idea was always that it would have a stealth bomber kind of look. Plus, the panel had a strong identity. The original color was black and ended up being more of that metallic gray kind of finish. I think we revised which parameters would be on the panel and how we laid the sliders out. I remember discussing where the Tone select buttons should be. It was nice to have input on some of that stuff.

Shimmer, Presence, and Bias

The layout was a simple concept with some brilliant touches. Controls related to the digital parameters of the instrument were on a 45-degree angle. The subtractive controls were in the center vertically.

You can see everything all at a glance and program very quickly. It’s always been one of the best feeling instruments to make sounds with. What was interesting is how many parameters there are for bias. It looks hilarious now because in today’s synth world, no one even knows what bias is! Even digitally-controlled synths and virtual synths have more traditional analog-style layouts.

We were all about stretching those samples to the extreme ranges, so they wouldn’t hurt your ears. They’re clean and pristine. There was also something really magical about the D/A converter circuit we used. The JD-800 has this kind of shimmer and presence. Even now, when you turn it on, it sounds great.

"The JD-800 has this kind of shimmer and presence. Even now, when you turn it on, it

sounds great."

Limitations Lead to Innovations

With the D-50, you took advantage of design limitations to create some incredible sounds. Did this also happen with the JD-800?

We were trying to correct some things about the D-50, like not having filters on your PCM, as well as not having multisamples. We didn’t have much memory, so we couldn’t do a whole lot. But at least we could create multisample waveforms that track a keyboard well and are useful across the whole range.

"I remember the challenge of trying to make a piano that only took up one megabyte, a fourth of the memory."

Were there idiosyncrasies you were able to exploit and become something unique to the JD-800?

Technology had progressed to the point where we didn’t have to think quite like that. Probably the biggest thing I remember thinking about was doing the same thing we did with the D-50 with the one-shot attack samples. We changed that and decided to loop everything. That way, even the sampled waves that had an attack transient would have a sustain portion as well—when it would go into a single-cycle loop. This ended up being useful because you could freely use them on any of the four tones as either sustaining sounds or attacks.

I remember the challenge of trying to make a good-sounding piano that only took up one megabyte, a fourth of the total memory! It was hard, especially because we were working at 44.1/16-bit. Still, that piano had a vibe. It doesn’t sound like an acoustic piano, but it’s a useful piano-type sound.

In the Cards

Did you also work on the SL-JD80 ROM Cards where strings and other acoustic instruments start to appear?

Yes, we did all of those cards at that time. In fact, back then all of the sound development for the pro-level instruments was based out of Roland R&D Los Angeles. The ROM cards weren’t as preplanned as the JV series. With those, we had a whole roadmap of where we were going. The JD-800 had no drum sounds, so it was a big deal to be able to add drums to it via that expansion card slot.

Classic Cuts

On the Genesis tune, “I Can’t Dance,” Tony Banks uses a JD-800 preset. Were there any recordings where you thought, “That’s the instrument in its glory, boys”?

That was also back when I was doing most of my work as a session player in Los Angeles, so my first thought is of all of the wonderful recording sessions that I used the JD-800 on myself. It was absolutely one of my favorite instruments! My favorite memory is working on a Marcus Miller record. He and his manager had an office on Sunset Boulevard that was a little house. There was no air conditioning, so it was incredibly hot. We had all the windows open, which was odd for a studio. You heard Sunset Boulevard right outside the window.

Marcus had a twenty-four track in his backroom. I brought all my racks in there and, of course, the JD-800 was one of the main tools I used. We were working on the album-closing song, “The King is Gone,” his tribute to Miles Davis. Marcus wanted it to sound like a funeral dirge.

"I’ll never forget sitting there with the JD-800 creating that sound while Marcus paid tribute to his hero and beloved friend, the great Miles Davis."

He’d sequenced the chords, and I was working with the data and got lost in it. I was hearing all these traffic sounds and screaming, sirens. Suddenly, from behind me came this incredible woodwind voice. Marcus was playing the melody on a bass clarinet in the room. We were a foot apart. I didn’t even know that Marcus played bass clarinet! When he played the melody, it was so transporting.

I’ll never forget that incredible moment, sitting there with the JD-800 creating that sound while Marcus mournfully paid tribute to his hero and beloved friend, the great Miles Davis, who had just passed away only weeks before. It was a sacred space and there were no words between us—like being on Holy Ground. I really felt humbled to be there and that I was getting to be part of music history.

No Sound Left Behind

Is there anything that you hoped to do with the JD-800 that ended up on the cutting room floor for reasons of budget, time, or not fitting the theme?

Memory was the big one. We only had four megabytes, and it was a sample-based synth. That meant all the sounds had to be one-shot waves. Later, you got longer waveforms and loops, more velocity switching, and more sophisticated sampling. All we had was multi-sampling, and because of the memory limitations, we couldn’t go crazy.

However, in terms of design, I was really happy with how it came out. The JD-800 felt like a fully-realized instrument. The effects sounded good and were flexible. The interface was wonderful and it spurred you on creatively. You didn’t feel limited, even though the limitations of the waveforms were significant. Plus, you had all those LFOs so you could move the sound around a lot.

"The interface was wonderful, and it spurred you on creatively. Plus, you had all those LFOs so you could move the sound around a lot."

Finally, does anything else stand out from that period which synth fans may find interesting?

There’s one thing I remembered when talking about those ROM cards. I forgot that I did a signature 100-patch card for the Japanese market. It wasn’t available anywhere except Japan. A couple of years ago at the NAMM show, someone came up to me and had one. I signed it for them, so that was pretty cool. If somebody’s got one of those little babies, they’re ultrarare now and a genuine collector’s item! I have to say that overall, the JD-800 project we did together was an absolute blast and honor to be part of.