The journey of an instrument from initial idea to its eventual physical manifestation incorporates many voices. From the technical engineers to product managers, each personality, opinion, and specialization helps shape the outcome of a creative project. In the case of the TR-1000 Rhythm Creator, the first Roland drum machine in four decades with a true analog engine, this chorus of perspectives included another critical group: artists. The Engineering team garnered powerful insights by road-showing the TR-1000 and engaging music makers who have long supported Roland gear. Product Leader, Peter Brown, gives a behind-the-scenes look at how the TR-1000 integrated input from the creative community into the final product.

Lessons Learned

Previous Roland instruments became iconic successes after their commercial failure, and pioneering artists are largely to credit for this. What lessons from this influenced the TR-1000?

There’s probably a limit to which you can design instruments to fit a specific workflow, but in the end, the artist will find their own way to use them. These days, instruments are so deep, filled with features and comprehensive workflows, but I’ve spent years meeting users who only use a fraction of them, even after eight years. It’s not a bad thing, though. It encouraged us to make the features more digestible and easier to discover.

Removing Guardrails

As a product manager, what felt important to capture for rhythm creators, and how did you approach it when meeting with artists around the TR-1000? Did any TR stories stand out?

Spontaneity and happy accidents, especially with sequencing. I think it was Terry Hunter who told us about how people would pound random rhythms into the 909. Since it was always quantized, it would spit back interesting rhythms—that and removing guardrails on the sound engines, allowing things to sound “bad” or unpredictable. Many folks want to hear the sounds get pushed “too far.” This leaves it up to the user to decide the limit of what’s usable or not. Maybe when it sounds the most extreme, we just haven’t heard those sounds used in music yet.

"Many folks want to hear the sounds get pushed 'too far.' This leaves it up to the user to decide the limit of what’s usable or not."

What artists were part of the TR-1000 development process?

There was a great mix of frequent collaborators and newer folks. We had lots of early conversations in Detroit. Artists in Underground Resistance, BMG, and Aux 88. Satoshi Tomiie, Kuniyuki, and Hisashi Saito dedicated a lot of their time to testing early prototypes of the sound engine.

In Berlin and the UK, we showed off early versions to Overmono, Leonard de Leonard, Floating Points, and other folks. It wasn’t always a homerun. We digested all sorts of feedback about workflow, the design, the sampling, etc. Working artists or folks making their primary source of income producing music are least likely to abandon tools they know inside and out. Nobody is paying you when you are learning a new instrument. It motivated us to design the TR-1000 to be familiar (TR-style interface), while adding new elements that fix something or make things easier for them.

Reactions and Requests

What were some of the initial reactions from musicians about Roland creating its first analog drum machine in forty years?

To some artists, it was certainly exciting. Plugging in and playing even just the 808 hi-hats alone brought some big smiles—those who hold fidelity in high regard. For others, the digital side was way more compelling. Hearing the modified 8X and 9X tones was so refreshing, especially for artists so used to hearing the same tones for decades. Satoshi Tomiie put it best: “It’s like an 808, but different.” That alone was hugely inspiring.

You have a history of working with artists on developing products like the SP-404MKII and others. How was this process unique?

The MKII already had a rough blueprint made for us, just through community feedback alone. Of course, we spoke with artists as well to get detail and nuance. The TR-1000 conversations were way more exploratory. The market is also more spread out, so we traveled a good amount to try to see each artist’s studio and how everything was set up.

What feature requests came up repeatedly in early conversations with artists?

Sample chopping and incorporating drum breaks with analog/digital tones. Initially, we didn’t have non-destructive sample slicing, but that was a big request in the context of making things fast and fluid.

"The market is spread out, so we traveled a good amount to try to see each artist’s studio and how everything was set up."

Counterbalance

Walk us through what a development meeting with musicians is like.

They’re completely different in Japan compared to the rest of the world. In Japan, an entire afternoon is scheduled at the R&D center. Each sound is reviewed in the studio or auditorium, and each parameter is tested. Everything is thoroughly examined. The patience of these artists is astounding. In the US and EU, it’s way more free-form.

Once the standalone prototype made noise, we would hook it up and start making sound immediately, full-on. Seeing how the instrument fairs when thrown into a studio or session cold with little prep was a great contextual counterbalance. The artists tend to focus on the areas that interest them, so that some meetings would be exclusive to analog sound, with others the sampling, etc.

Did some added enhancements (such as expanded pitch and decay ranges, and tunability) emerge from your talks? How did musicians react to virtual analog modeling, FM synthesis, VA waveforms, and PCM features?

In Detroit, the artists kept telling us they wanted to “freak the sound.” We had to take that sentiment and make it real. While the analog sounds can be molded inside the sound engine, creatively automated, and sequenced, this is where the digital component really shows its strength.

There’s one tone that I love showing off. The 9X Rim Shot takes the 909 Rim Shot and breaks each component apart into its own voice. It’s actually three oscillator layers combined, so each layer’s tune and decay can be independently controlled.

I would start with the core sound settings, which the artist would presumably have heard thousands of times, and slowly deconstruct them in real time. It breaks a fourth wall—you hear this time-tested sound start to mutate, and you get to understand it on a deeper level. Most of the time, the reactions are like “Whaaaa?” or “Woaaahhh!”

"In Detroit, the artists kept telling us they wanted to 'freak the sound.' We had to take that sentiment and make it real."

Mod Life

Of all the new features, the circuit-bent 808 and 909 voices feel very much in the spirit of listening to Roland fans. Did you see some modded units?

Satoshi Tomiie had a modded 909 with a great sound character. We studied and compared it to our analog and digital prototypes. We also listened to units that had strange character—not modded, but for whatever reason, they came out of the factory sounding wonky.

There’s so much subjectivity regarding what sounds “good” or “like a X0X.” ACB’s initial mission was to create a median sound with just enough control to achieve an ideal result. In the process, we built these DSP models with a high degree of modularity. This made the “digital circuit bending” process possible for normies like me who are not DSP engineers to tinker around and see what sounds interesting.

"The aesthetic was heavily inspired by UR’s feedback, wanting less bright and in-your-face colors, something more stoic."

Finding the Look

Did artists have input into the TR-1000 aesthetic in terms of color, knob layout, and general design?

Definitely. The aesthetic was heavily inspired by UR’s feedback, wanting less bright and in-your-face colors, something more stoic. We also had early versions that had slightly different layouts and spacings. At one point, the Morph fader was perfectly in line with the step sequencer, and I think Shawn Rudiman pointed out that it was a dangerous spot, likely to get moved by accident when people did the finger-drag trick to program all of the steps at once.

What were your most positive memories of traveling and developing the TR-1000?

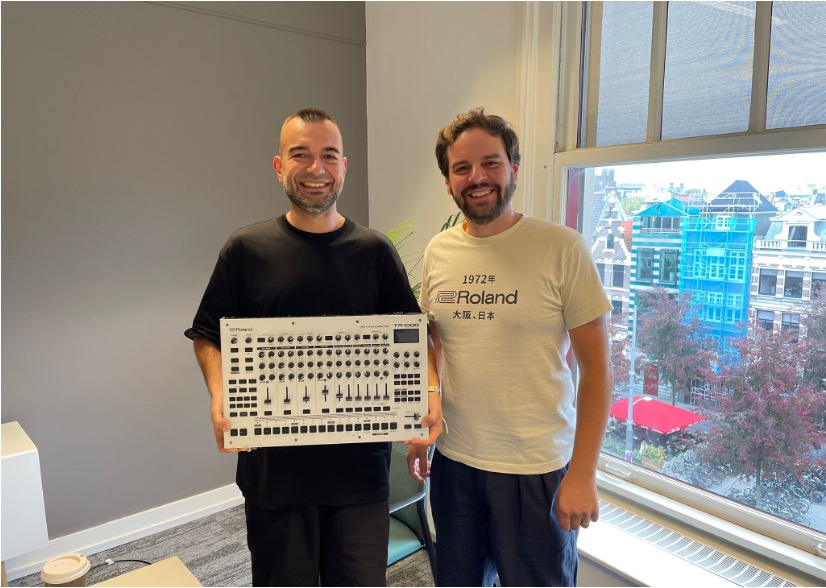

Regarding marketing activity, we had an activation in Amsterdam at ADE last year. We hosted about 40 artists at a small coffee shop called Black and Gold. It felt like the perfect audience for the product. Everyone understood it right away and was asking the right questions.

"My team got to be creative and blue-sky in a way that’s impossible with other products. The 'try it and let’s find out' mentality felt refreshing."

The early development of hacking ACB and prototyping the analog was a blast. My team got to be creative and blue-sky in a way that’s impossible with other products. The “try it and let’s find out” mentality felt refreshing. Ishimine, one of the development leaders, said the project had a “new smell” (新しいにおい). Fun fact: He was the lead on the TR-727, so it’s kind of a cool full-circle moment for him.

The analog development was more focused, but also a lot of fun. We had quite a few sessions in the listening rooms in the Hamamatsu factory, comparing the characteristics of four or five machines. Having to decide the direction of the analog sound/parameters with given constraints was like trying to solve a morphing puzzle in the best kind of way.