In 1984, the airwaves brimmed with Bananarama and Billy Ocean, intermingled with hits from the Footloose soundtrack. Yet, far beneath the mainstream, in the basements of rainy Vancouver, British Columbia, a grimy new style was brewing. Drawing on elements of electronic music, noise rock, gothic melodrama, and even the bombastic beats of hip-hop, Skinny Puppy created something utterly new and utterly terrifying.

An Influential Debut

Skinny Puppy’s debut, Remission, was initially released as a six-track 12-inch EP and later expanded to a full album. Its noisy industrial sound, characterized by distorted vocals, sampled sounds, and pounding percussion, paved the way for the crossover successes of countless black-clad combos.

In fact, Remission’s abrasive tones and uncompromising lyrical messages predated—perhaps even inspired—Ministry’s visual transition from synthpop dandies to their famous “dreads and combat boots” aesthetic.

And it all started with a drum machine: the Roland TR-909. While the 909 is heralded for its use in pop and dance grooves, Remission is often cited as one of the first recorded uses of the gray beatmaker. Opener “Smothered Hope” kicks off with a sledgehammer 909 beat: a broken-down pattern made up of sizzling hats and distorted kick far removed from the band’s contemporaries.

Core Membership

Although Skinny Puppy would develop into a revolving lineup, at the band’s core were instrumentalist cEvin Key, vocalist Nikek Ogre, and producer Dave “Rave” Ogilvie. Speaking from his studio in Vancouver, BC, Ogilvie shares how that genre-defining drum sound evolved.

“The funny part about that whole thing,” recounts Ogilvie, “was that we spent $5,000 on some gear including a 909. We’d been working with the TR-808. All of a sudden we had this brand-new gear which was state of the art at the time.”

He goes on to explain that while Roland had already been part of their sound, the 909 was a whole other animal. “At first we turned on the 909 and it was far too clean. We were like, ‘What have we got here?’ I struggled and was very stretched for ideas.” Inspiration came in the unlikely form of a PA system. “I was looking around the studio, found a PA crossover, and took the three outputs from the kick into the board. Now, I had three kinds of specific frequencies that I was able to mess around with.”

It was a eureka moment. “All of a sudden we were like, ‘Wait a minute. This sounds brilliant now.’”

“By this point, we were in love with the TR-909 going, ‘OK, we have something different and we want it all over the record.'"

The Turning Point

Ogilvie’s unexpected treatment of the 909 became the turning point for the album. “We went from complete frustration to, by splitting the frequencies and being able to mix them separately, coming up with our unique version of the 909.”

Adding effects to the TR-909’s snare resulted in another breakthrough. “At Mushroom Studios, they had two wonderful acoustic chambers—big tall, skinny ones. I ran the snare through the chambers, and once again we got this awesome sound.” The 909 became central to what they were building. “By this point, we were in love with the machine going, ‘OK, we have something different and we want it all over the record.’”

That sense of adventure is what drew Ogilvie to the world of production in the first place. “I’d drive around listening Talking Head’s Remain in Light and Brian Eno and David Byrne’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts,” Ogilvie recalls. “I’d hear all the layers—the noises and pads. I tried to dissect them all and realized I enjoyed thinking about how the whole thing goes together.”

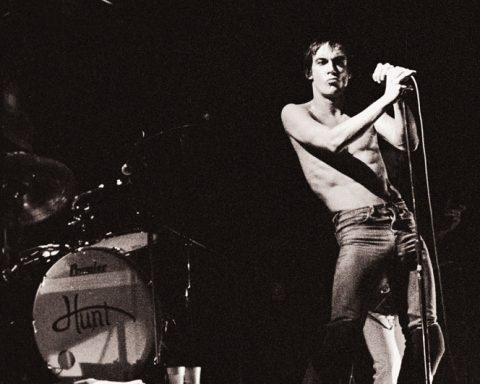

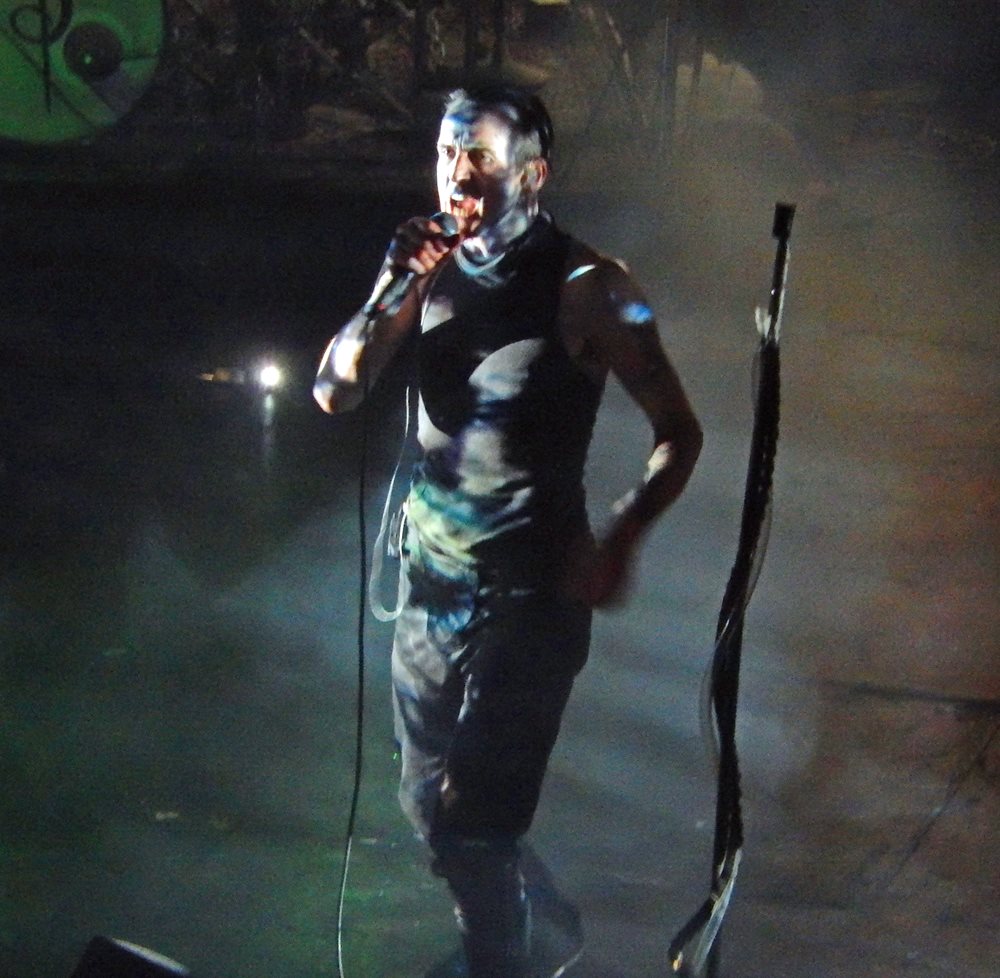

Enigmatic Frontperson

In the case of Skinny Puppy, what brings it all together are the lyrics and vocals of center stage provocateur, Nivek Ogre. Sometimes mistaken for mere misanthropy, Skinny Puppy’s songs frequently dealt with animal rights and environmental concerns. Helmed by Ogre, the band’s highly theatrical performances amplified their politics using groundbreaking—frequently graphic—visual media and costumes.

“You had to make decisions. It was generally cEvin and I with four hands on the board. The whole record was based a lot on performances.”

So, what were Ogilvie’s first impressions of Ogre? “He was a very shy, timid guy,” says Ogilvie. “I cracked up because we both had the same last name. I was like, ‘How did this happen?'”

The fast and furious approach to recording Remission meant little time for overthinking, which suited Ogre’s instinctive vocal style fine. “There was no putting down 17 tracks and comping. Every time he’d do a new vocal, it was a performance. He would do a take and, generally, the first would be the one.”

The live effects processing on Ogre’s vocals added dynamic layers to the record. “You’d solo them and hear how much character they would add to the songs. It was just brilliant.” As for the trademark distortion on the singer’s voice, well, that had a less technical explanation. “It got treated a bit after,” explains Ogilvie. “But a lot of distortion you hear is his actual voice.”

The Benefits of Analog

Despite using electronic instruments like the TR-909, Ogilvie insists that the spontaneity of the analog recording process was a key factor in the Remission’s energy. “You had to make decisions. It was generally cEvin and I with four hands on the board. The whole record was based a lot on performances.”

Did they expect the album to become as influential as it did? “No, but we were excited about reaching out to the world. Soon we were doing tours throughout the States, across Canada, and in Europe, which was incredible at the time.”

In addition to the power of Remission, Skinny Puppy’s visceral live show certainly contributed to the groundswell of interest the band received out the gate. “Our attitude was the show has to be different. It has to be special and if we make any money on anything, it all goes back into making a better show.”

On albums like Too Dark Park and Rabies, Skinny Puppy gained even more notoriety for its controversial, compelling music. In turn, Ogilvie’s involvement in shaping the band’s sound led him to work with Al Jourgensen of Ministry and Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor.

“The first record was so much fun because it was done on a shoestring budget in the middle of the night. We had a really, really good time."

Mardi Gras and Marilyn Manson

One such notable project with Reznor was Marilyn Manson’s Antichrist Superstar. “The Manson record was a fantastic experience from the aspect of just making art. That was the first co-production I did with Trent. We started with demos they sent us from hotel rooms and then we would work on them. We had fun at Mardi Gras, then hid for three months. I would spend four or five days per song and then move on to the next one.”

Ogilvie remembers some unusual restrictions during that particular project. “We were not allowed to use any guitar amps at all, plus every song had to be different. They were big fans of the Zoom pedal—they loved that sound. Luckily, Trent had an extensive selection of guitar simulators. That pushed me out of my comfort zone.”

Still, with all the albums he’s helmed and influential artists he’s worked with, Remission retains a special place in Ogilvie’s memory. “The first record was so much fun because it was done on a shoestring budget in the middle of the night,” he laughs. “We had a really, really good time.”