Tom Scott is a three-time Grammy-winning saxophonist, composer, arranger, producer, and digital wind pioneer whose prolific career has spanned more than five decades. As a founding member of the L.A. Express, Scott has collaborated with a vast array of artists, including Joni Mitchell, Steely Dan, Quincy Jones, Dan Fogelberg, and more. Known for his blend of jazz, pop, and R&B, his iconic saxophone solos can be heard on tracks like Michael Jackson’s “Billie Jean” and “Black Cow” by Steely Dan.

In addition to his work in the studio and on tour, Scott has composed numerous film and television scores, including themes for Starsky & Hutch and Family Ties. The multi-faceted musician discusses lessons from his storied career, his Aerophone journey, and how to pursue musical passions.

Slipping into the Business

Your father was a film and television composer. How did growing up in that environment shape your musical journey?

I was surrounded by music from a very early age, and I consider it a great stroke of luck that I was born into such a musical family. My mother was a classical pianist who accompanied several opera singers in her earlier years.

My father had a wonderful record collection that included classical music. I remember buying the score to Rites of Spring and attempting to conduct to the recording. We also had recordings by Sinatra, Nat King Cole, Ella Fitzgerald, and a lot of big band stuff. I didn’t have to travel far to find good music.

I started playing the clarinet in elementary school. My dad bought me a famous 1938 recording—Benny Goodman and his Orchestra at Carnegie Hall. My parents’ friends included great musicians, actors, and others in show business. I started playing private parties, bar mitzvahs, and weddings at the age of 14. By the time I was 18, I was working as a studio musician. I was pretty well prepared.

Super Mentor

Tell us about the role legendary composer John Williams (Superman, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Star Wars) played in your career.

My father composed, orchestrated, and conducted dramatic scores and amassed over 700 credits in films and television. He wrote underscore for shows such as Twilight Zone, Dragnet, Wagon Train, Laramie, My Three Sons, and all the music for Lassie during its last 12 years on TV. For many years, the dining room in our house was his office—with a piano and a drafting table.

I was hired to play in the orchestra for a TV special called Movies Rock. The show introduced famous movie themes from the past to a more contemporary audience. For example, John Legend sang “As Time Goes By” from the movie Casablanca.

John Williams walked into the room to conduct a medley of famous instrumental movie themes. He came straight over to me and offered his condolences on the recent passing of my father. He said that in the ’50s, when he was a full-time studio piano player, he decided to try composing for film and television. My father, he said, was the supervisor for his very first assignment, and one of the primary reasons he decided to pursue it after that was due largely to my father’s kindness and encouragement.

Electronic Wind Pioneer

You’ve been a pioneer in using electronic wind instruments like the Lyricon. What drew you to these instruments, and how have they influenced your musical expression?

As a studio player and composer, I was always seeking new tonal colors. That’s the way I viewed the Lyricon. I was on tour with Joni Mitchell in 1974. I opened a copy of DownBeat magazine, and there was a quarter-page ad with this metal clarinet-looking thing, along with the name and number of the factory located outside of Boston.

I called and asked, “What is this thing?” They described it as a wind synthesizer that translates wind volume into voltage, just like pressing a key on a synthesizer does. It was a revolutionary idea at the time.

I got to Boston, went to the factory, got one, and I loved it right away. I love the way it adds to the palette. I started using it on a bunch of recordings. I did an extended solo on a tune by Dan Fogelberg, “Heart Hotels.”

In terms of blowing, it’s a lot easier than playing the saxophone, flute, or any woodwind instrument because it doesn’t take that much wind. It’s designed so you just put enough air in to trigger it and are good to go. The Lyricon opened a whole new world.

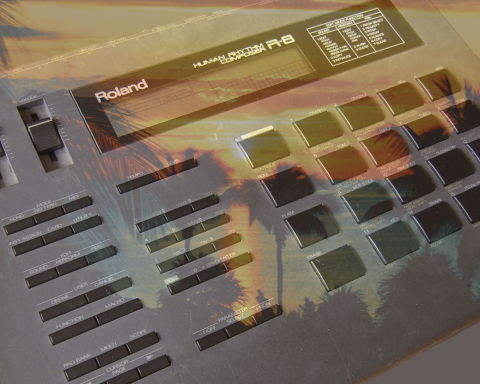

You’ve become a big advocate for the Roland Aerophone. How does the instrument enhance your performance?

The Aerophone enhances my performances because it opens up a whole world of sounds—amazingly, there are over 600 of them. And there are dozens of sounds on the Aerophone that I love.

"Aerophone is my second, third, fourth, and fifth instrument. It’s many instruments in one."

Aerophone Expert

Are there any favorite tweaks or settings that you use to achieve your signature sound?

I sent Matt Traum—our wonderful programmer and a great wind synth performer—the most important one. I told him I was looking for a sound on the Aerophone that wasn’t there, and I sent him a recording of the Lyricon sound.

He waved his magic wand—his magic programming tools—and sent me the sound. I asked if he could make it a little more edgy. He said, “Tom, you know that Aerophone app you have? You can edit all this stuff yourself.”

So, I started tweaking. I’ve got that Lyricon sound he created for me, my little variation, muted trumpet, jazz scat, vibes, and organ. I don’t need much more than that when performing with my band.

There’s saxophone, and there’s Aerophone. Aerophone is my second, third, fourth, and fifth instrument. So that’s the thing about it. It’s many instruments in one.

With a career spanning thousands of recordings and live shows, how does your approach differ when recording in the studio versus performing live, especially when using instruments like Aerophone?

In a certain sense, there’s not a lot of difference between recording and playing live, because the goal is to provide whatever a particular tune calls for. It’s the same in front of an audience or in a recording studio. I don’t see that dichotomy. Obviously, it’s a different ambience; in one, you’re in a room often alone, and in the other, you’ve got an audience sitting in front of you. However, the process of making music remains the same either way

"Quincy Jones was so kind and encouraging [to me] and helped promote my career."

Genius Meets Genius

Can you share some memorable experiences or lessons from Quincy Jones that left a lasting impression on you?

I’m delighted to have known and been the beneficiary of Quincy Jones’ friendship. Quincy Jones was so kind and encouraging and helped promote my career. I did a recording session for him when I was probably 19 or 20.

I remember opening an issue of the Los Angeles Times Sunday Calendar. There was a jazz critic named Leonard Feather who used to do a Sunday jazz column every year, and in 1968, he interviewed Quincy, asking him to name some up-and-coming musicians. He said, “There’s this 19-year-old woodwind genius named Tom Scott.” I didn’t think of myself as a woodwind genius, but it was extremely flattering to have Quincy Jones say so in print.

I arranged and played for him for a few years. In 1973, I got a call from Quincy. “My friend Sidney Poitier just directed his first movie called Uptown Saturday Night and asked me who should compose the score. I gave him your name, and he’s waiting for your call at MGM.”

That turned into a wonderful relationship. I composed scores for three Sidney Poitier movies. Sidney and Quincy were both very classy guys.

TV Eye

You’ve also composed for shows like Starsky and Hutch and Family Ties. How does composing for visual media differ from your other musical projects?

If I say yes to a musical assignment, my goal is always to put forth my best efforts. The craft of composing for television and film is a separate skill. However, the goal is the same as recording—to enhance the film or TV show by providing the right music. The music has to serve the film, and often, less is more.

"When I was first starting as a teenager, I wanted to surround myself with better players than me. They kicked my butt—and in doing so, made me a better musician."

Others may describe me that way, but I’m reluctant to call myself an artist—it sounds a bit pretentious. I prefer to think of myself as an excellent craftsman. And that includes playing on someone else’s record, my own record, writing film or television music, whatever. I’ve worked hard to be good at my craft.

I’ve surrounded myself with all the best people I could find. In fact, when I was first starting as a teenager, I wanted to surround myself with better players than me. They kicked my butt—and in doing so, made me a better musician.

Becoming a Blues Brother

You played a key role in shaping the iconic sound of the Blues Brothers. What was that experience like?

I was a big fan of Saturday Night Live. I saw one segment—the debut performance of what became the Blues Brothers. They were doing a spoof on Roy Orbison with their outfits—the suits, the hats, the sunglasses. They hadn’t fully developed the characters, but they were still very funny. It’s funny, comedians want to be musicians, and musicians want to be comedians.

In the meantime, I was in LA and read that the Blues Brothers were opening for Steve Martin at the Universal Amphitheater for a week. I thought, “I’ve got to get backstage.” I had a couple of friends in the band who I hoped could help.

They didn’t need to, as it turned out. Two or three weeks before the performance, horn player Tom Malone called me and said, “Listen, Tom, my wife is having a baby right in the middle of that week at the Amphitheater. Can you sub for me for the first two days?” I said, “Hell yeah!”

I showed up on Monday afternoon, met John [Belushi] and Danny [Aykroyd], who were very nice, and the band was kicking. We had a thirty-five-minute show. It was so hot. We did Monday and Tuesday, and sure enough, Wednesday morning, the Malones’ baby was delivered, and he was on his way to LA from New York.

I assumed I’d hand off to him and say, “Man, this was great, thank you so much.” But John Belushi walked up to me and said, “Tom! I’ve decided we’re just going to make it four horns instead of three. You’re a Blues Brother.” And with that, I became a Blues Brother. I was very close to John and Danny; in fact, Danny is the godfather of my son.

"I didn’t know I could be a successful pro in the music business. I just loved music, specifically jazz. And I just couldn’t imagine myself doing anything else"

Talk About the Passion

What advice would you give young musicians aspiring to have a rich and enduring career like yours?

It’s about passion. If kids ask what it will take to become a professional musician, I first say that the music business now is a universe away from what it was when I was young. Social media is the driving force behind careers today. So, I can’t address the specific ways you can earn a reputation and support yourself as a musician. Your path will necessarily be a lot different than mine.

You’ve got to ask yourself, for whatever instrument you play, whatever you aspire to be, who is your favorite person on that instrument? Ask yourself, “Do I have the talent and the drive to do what it takes to get to that level?” If you honestly think you can, then go for it. It will be a tough road, and you may not have much money for a while. But if your passion is there, then I say go for it.

On the other hand, if you ask yourself those things and say, “I don’t know if I have the drive to work that hard,” or “I don’t think I have the talent to be that good,” then it’s great to have fun with music.

I didn’t know I could be a successful pro in the music business. I just loved music, specifically jazz. And I just couldn’t imagine myself doing anything else. You’ll need that kind of dedication, regardless of the difficulties, to achieve your goals.

Do you have any upcoming projects or collaborations you’re excited about?

I just finished a PBS American Masters series honoring director Blake Edwards. He was married to Julie Andrews and wrote and directed, among other things, the Pink Panther movies. I composed, performed, and sequenced the entire score.

"Whatever the project might be, I’m delighted to still be active—I just turned 77."

The L.A. Express is back. We’re doing some weekends now. We sold out our 50th reunion at the Baked Potato, the North Hollywood club where it all started. I’ve got four marvelous new players performing many of the original tunes. We were among the originators of “funk-jazz.”

I still do a lot of playing and arranging, including some “vanity projects.” People who have money and want to make a record come to me to provide a sax solo, a horn arrangement, or whatever. They send me the track, and I do my thing and send it back. I’m in the middle of one now. But whatever the project might be, I’m delighted to still be active—I just turned 77.