You may or may not know it, but you’ve probably heard Pete Korpela. It may have been on a major motion picture soundtrack (Avatar 2 and 3, Spiderman: No Way Home), video games (Assassin’s Creed series), TV (The Mandalorian), a beloved production (The Lion King 2019 film score and first national tour), or on arena tours with Josh Groban. Regardless of the context, this classical and contemporary percussionist is high on the call sheet of major composers, producers, and artists who need a variety of styles and sounds—and quickly.

For the past three decades, the Finnish percussionist has traveled all manner of distances, fearlessly sought out mentors, and learned Afro-Cuban to symphonic instruments without ceasing to answer the call when it came. Learn about Pete’s original inspirations, how relationships are foundational to everything, and how to show up for every gig.

One-Way Train to Music

What were your earliest musical inspirations?

There was a music class in years 3-9 of school, where you would get an hour of music every day. Everyone had to audition. The school selected 30 students every year, and then there would be harmony, theory, and choir. We all had to learn an instrument based on availability, what was needed, or what we wanted. I was originally assigned the French horn.

So, I started learning French horn but continued begging and just being a pain in the ass to my parents. I wanted a drum set, and finally, they bought me a kit when I was probably in 3rd grade. However, the rule was that I had to take lessons. I couldn’t just play rock or whatever. I had to study to learn how to play.

Throughout those years, the school would take us to watch the local symphony orchestra. I remember watching all these live musicians perform onstage and having a connection that just grew. There wasn’t one moment; it was a gradual build.

Was there a moment you felt music was “it” for you?

I saw my old teacher, Mongo Aaltonen, play congas on TV with a famous rock band, and it just blew my mind. I was like, “This is what I want to do.” So, while my parents made me study classical music, all I wanted to do was play congas and hand percussion, and I had to travel to do it. Now, I was born and raised in the eastern part of Finland, and nobody there knew anything about hand percussion. I started taking a three-hour one-way train to Helsinki for lessons, which I did throughout my high school years. Then I auditioned and got into Sibelius Academy, a college in Helsinki.

"I saw my old teacher, Mongo Aaltonen, play congas on TV with a famous rock band, and it just blew my mind. I was like, 'This is what I want to do.'"

From School to Studio

How did your education help you set a foundation for building your craft?

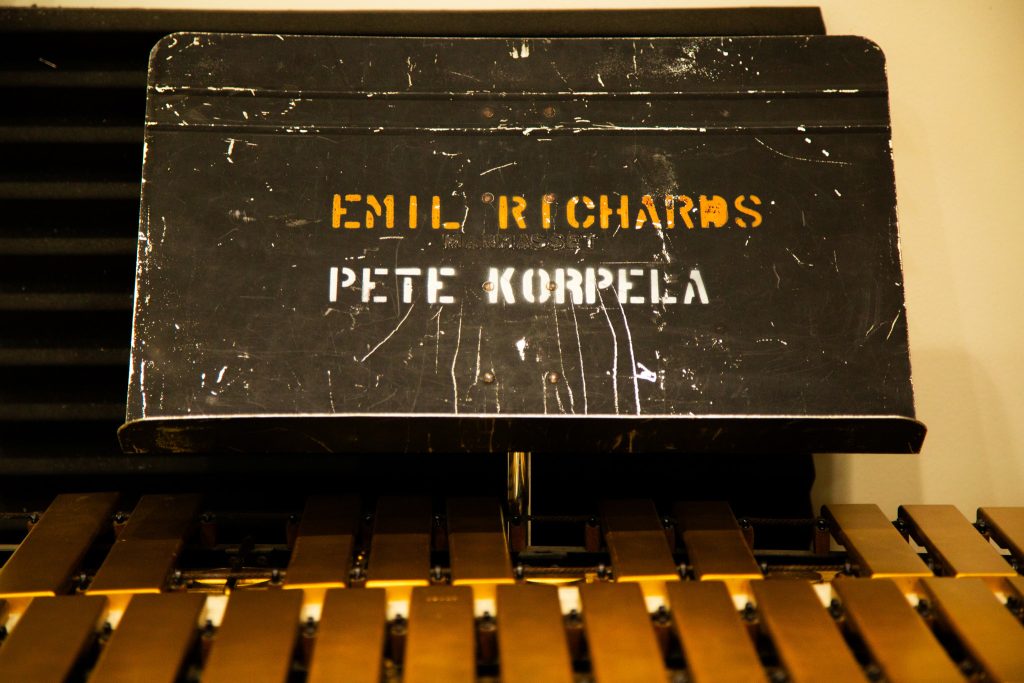

I was there for maybe two years, then that’s when I came to the LA Music Academy, now Los Angeles College of Music. It was a brand-new school back then, and Emil Richards, Joe Porcaro, Ralph Humphrey, and Jerry Steinholtz were the instructors. I was speaking with Drummer’s Collective in New York City about piecing together a hand percussion program for me, but then I saw an ad in Modern Drummer about a school in LA.

I was the only percussion student at LA Music Academy, so obviously, I got a lot of attention, but there was also absolutely no way to skate by. I was under a microscope. If I practiced and showed up prepared, it was good. If I didn’t, it wasn’t. And they were not shy to let me know.

Can you describe the path from graduation to a touring and working studio musician?

Well, I knew I wanted to be a studio or session musician more than a band member. That lifestyle keeps me inspired and pushes me to the next level, because to make a living as a full-time session musician, you have to adapt.

So, I attended the one-year program, and there was an instructor, Jerry Steinholtz, who knew everybody in the industry. And when I was a 20-year-old student, we would go to PAS (Percussive Arts Society) or NAMM, and he would introduce me to all these players and artist relations departments. When I graduated, I reached out to these reps and went to see players at different clubs in LA. I’d reintroduce myself, help them break down gear, and ask for lessons.

I spent a few years in Finland after graduating, but I came back to LA in 2000, focused on studying. That’s when I started taking lessons with Kevin Ricard (Dancing with the Stars, America’s Got Talent), Michito Sanchez (John Denver, Joao Gilberto), and LA studio legend Don Williams. All of them had played on TV shows, huge tours, and sessions, and their careers were peaking. I’d go into lessons with specific questions like, “What was that thing that you were doing in that song? Were you using this instrument or that instrument, etc.?”

"I was laser-focused on getting the information I wanted, but after studying with them for an extensive period, they knew my strengths and weaknesses."

A good example comes from the symphonic world. Many orchestral percussionists are exceptional on Western classical instruments, but not everyone regularly plays hand percussion. When a program includes works that really require that specific background, orchestras often bring in a specialist. Just recently, I played with the LA Philharmonic on congas; not because others couldn’t do the job, but because Matt Howard (principal) wanted someone who is comfortable and experienced with that instrument in that particular situation.

I was laser-focused on getting the information I wanted, but after studying with them for an extensive period, they knew my strengths and weaknesses. They helped me build the skills I needed. Ultimately, the more you can play, the more valuable you are to the artist, the composer, or the contractor, the more you’ll work.

A 20-Year Overnight Success

What types of timelines do you typically work with, from contact to tracking?

It varies. Most work comes in very late these days, like within, let’s say, two weeks. A lot of stuff is within 10 days or a week. You get a call, and you’re available or not. If you are, then you get the music, and you know whether you’re the principal percussionist or you’re section. Whoever is principal, it’s their job to be the quarterback, per se. They send all the instruments, make contact with the orchestration team or the music prep, and try to get parts to figure out what is needed.

Is there a specific process?

For section players, we might get a PDF folder, maybe the day before. It doesn’t mean that you know what you’re going to be playing, because the challenge is that a lot of things change. There are so many variables: they might put instruments in different places, you have to split parts between a couple of players, a couple of instruments. They add to the music all the time, or take out. You might not have time to run from orchestra bells to the xylophone because it’s on the other side of the stage, so we make plans to account for that.

And that’s the type of experience you can’t get until you’re there, but you can’t get there if you don’t have experience. So, if there’s less work, the competition is harder, and if you get a call, you show up and you don’t deliver, then that was your chance. And then they don’t want to see you ever again. And teachers will tell you that you’ll usually get major movie calls around 40, and I know this for a fact because I got my first major motion picture calls at 40. The wait is long, and there are no guarantees—and it took me 20 years to become an overnight success, like my mentor Don Williams always says.

"The wait is long, and there are no guarantees—and it took me 20 years to become an overnight success."

Just Say Yes

What gets you through the lean times?

Thankfully, I learned so many different styles that if one area slows down, there’s something happening elsewhere. For example, we had a busy September and October recording films, and now it’s a slower moment. But I have video game concerts happening, then I’m playing with Pasadena Symphony, and then some old friends who play flamenco stuff. All of a sudden, I’m doing something else because I’m free to take on other work.

My approach has always been to say yes to everything and then figure out later if I can make it or not. And if I have to cancel something, I make sure the seat is covered with a player as good or better. The least I can do is to be a professional and help ensure their gig goes well.

A Stamp on the Bandstand

What gear and instruments can’t you live without?

About 80 to 90% of what I play is acoustic instruments, but when I use electronics, it’s because I’m trying to match an exact sound, still played live instead of from backing tracks. Or I want to have the actual sample from the recording. If I use a sample, it’s because it sounds different from if I do it acoustically.

For this, I’ll often use a Roland HandSonic (HPD-20) because it has so many sounds and the ability to modify them, along with a wide range to pitch them up or down. And then at times I’ll use the Octapad SPD-30 for both live and in-studio because I like the versatile handclaps, tambourines, and shaker sounds. Both of these instruments help speed up my work process and can cover so much territory. Also, I did five world tours with the same HandSonic and Octapad units, and I never once had them not turn on. Ever.

Another instrument I’ve used live is the SPD-SX with a KT-10 kick pedal and an FD-9 hi-hat pedal. I’m excited to get into the new SPD-SX PRO because of the higher sample bitrate. My plan is to do a deep dive and then sample my instruments to build my own unique sample library using the SPD-SX PRO. So, in the future, even if I’m at a scoring stage, I’ll have my own instruments available in any session, even if they weren’t ordered.

"People were sold on the fact that it was humans approximating the machines and not the machines telling us what to do."

For LP acoustic drums, I have a set of Classic Congas and a Giovanni (Hidalgo) Palladium Conga 5-piece set in black. They are the gold standard of the conga sound, and if you play LP Classics, nobody is ever going to have a problem. When I was about 14-15, I picked up a set of Carlos “Patato” Valdes fiberglass congas in a pawnshop in Finland. Putting those drums onstage was the first moment I felt like a serious professional. Like I put a stamp on my spot on the bandstand, that’s how it felt.

Other tools I’ve used over the years are the LP Soft Shake, which came out in the ‘90s. They come in pairs, but I take three because they are lightweight and super easy to play. The three-shaker combo is my favorite because it is a bit louder and cuts through a mix a bit more. Another instrument is the Black Beauty Cowbell, which has a consistent, signature high-pitched tone.

I also probably have about 80 tambourines and always take lots to any job. This ensures that if something sounds off, I have options. My favorites have brass jingles (Cyclops Handheld Tambourine), which have this round, warm tambourine sound. And lately, I’ve been enjoying the new LP Riq and Frame Drums—they’re just fantastic. I guess the beauty of the LP sound is that they’re so well recorded that they’re almost universally accepted.

Learn Forever

What’s your advice for young percussionists and composers seeking a lasting creative career?

Number one is that you have to study. You have to study and study, and you’re never done. You’re never entirely ready, so keep learning. You have to have that hunger to learn new instruments, take lessons, learn from your colleagues, and find mentors. I have had so many teachers. And a colleague of mine, Wade Culbreath, told me, “You used LA as your college.”

Listen to so much music. Old music, new music, current music, and all different styles. Seek out legendary musicians who recorded stuff and study them and understand what they did and why they did it. If you have a good teacher, they can explain what players are doing and why. Also, learn how to record yourself.

"Know when it’s time to just play, when it’s time to ask questions, and when it’s time to contribute ideas."

Invest in your instruments and buy the best possible gear you can get. Find them used on eBay or wherever you have to. For example, I was trying to find this old Ludwig tambourine from the ’70s and ’80s; I spent years searching for it. The instruments used can be why something works and why something doesn’t, so collect different instruments because, in a way, the more instruments you can play, the better you are.

People skills. Know what to do and what not to do. The “what not to do” is so important. Know when it’s time to just play, when it’s time to ask questions, and when it’s time to contribute ideas. But there are times when it’s not your time, it’s not your moment to do that yet. Be patient with that because you’re going to be working with experienced people who know a lot of things you don’t yet.

Also, show up on time—and I mean early—and be available to help other people. Remember that it is a marathon. You’re working with other people, maybe for a day, a week, or a year. But when it’s over, you’re back in the same pool with the same people. And if you behave unprofessionally, they will all speak to one another.