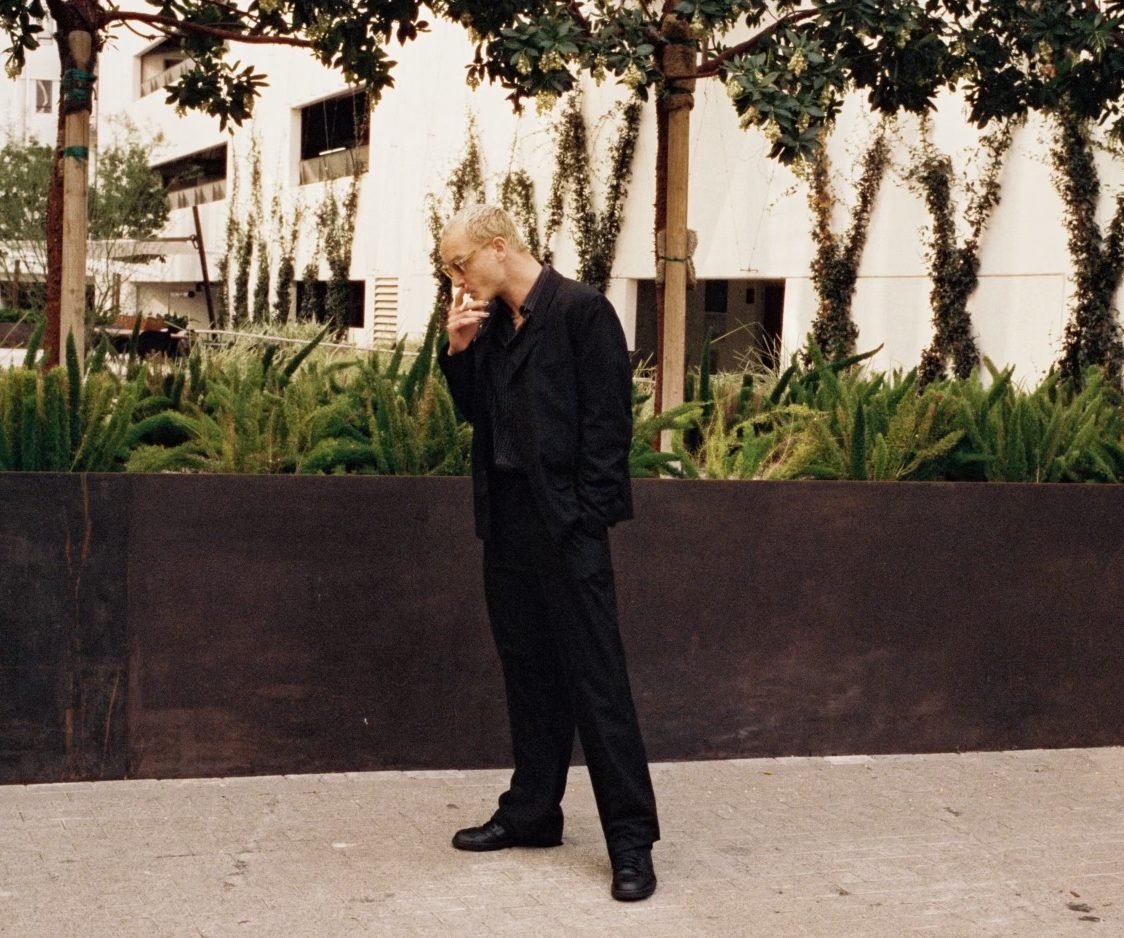

When George Daniel first joined The 1975, he immediately relieved songwriter Matthew Healy from the burden of simultaneously performing drums and vocals. The duo began writing together while Daniel moved further into the producer’s chair. Together, they’ve propelled the band to extraordinary success, racking up five consecutive No. 1 albums, including last year’s Being Funny in a Foreign Language. Daniel explains Roland’s vital role in the band’s achievements in the studio and on the road.

Percussive Perspective

Drummers are not typically involved in songwriting and production for vocal-based bands. Why was that different for you?

It’s funny, but I’ve always felt that being a drummer was never enough for me. When we started The 1975, Matt and I were hanging out in Wilmslow and making music whenever we could. But as soon as I went from living in a small town to the city of Manchester, I was immersed in a very different world and started making electronic music and producing.

As a drummer, is rhythm the foremost driver for writing and producing songs?

Very much so, and drummers are good at production because it’s paramount to understand the rhythmic feel of a song. At first, the tracks we made were very loop-based. Rather than use chords, the beats came in and out with lots of repetitious peaks, troughs, and lifts, and we knew that what we were doing had a certain simplicity and vibe.

"Drummers are good at production because it's paramount to understand the rhythmic feel of

a song."

Technical Curiosity

Did your inquisitiveness lead you to supplement your drum kit with electronic accompaniments?

As soon as I started going to gigs, I saw people playing with triggers, and everyone had Roland SPD sampling pads, which helped them transition toward a hybrid drum setup. I used them live for years and sometimes in the studio to pinch a few drum samples, but the studio-related stuff interests me more than live drumming.

Does being on the road necessitate using different technologies to help you write songs?

I wouldn’t be able to do what I do if I didn’t arrive at a time when everyone could afford to get a laptop. I learned music tech at college on a massive desk and an ADAT machine. But the software was getting cheaper, and plug-ins were getting better and better. That’s why electronic music is in such an interesting place, and producing on the road allows you to thrive.

Roland on the Road

How is the TR-8S useful while you are on tour?

The TR-8S is amazing because you can put samples on the SD card and sequence whatever sounds you want. It could easily go in a suitcase, and it’s bulletproof, so that will be coming out on the road with me soon.

Is writing on-location where the TR-808 and TR-909 recreations come into play?

I’ve never actually owned a vintage 808—they’re too expensive. But it’s funny how when you’re younger, you get so familiar with those drum machine sounds without actually knowing what they are. As soon as you figure out how to obtain one, you think, “My god, I can make music using the same sounds as everything I’ve ever heard in pop and dance music.”

But I’m not bored of the quest for the perfect 808 sound yet. That’s a lifelong journey. I’ve got the Boutique TR-08 and the TR-909 plug-in to create new samples. I’ve never made a record, or even a track, without reaching for one of those.

"I'm not bored of the quest for the perfect 808 sound yet. That's a lifelong journey."

Vintage Vibes

How do you use the D-50, one of the first digital synths to make waves?

Around the time we made The 1975’s second album, I did a deep dive into a lot of the music I used to listen to before I was into production. I got massively into Fleetwood Mac’s Tango in the Night, which is more synth and keyboard-heavy than their earlier stuff. I looked into what they were using, and the D-50 came up a lot.

We used a lot of FM synthesis on our second album. And, if I remember correctly, the D-50 was brought out to challenge that, so we transitioned away from the FM stuff whenever we wanted to make something sound more organic.

You frequently turn to the Roland JV-1080 as well, correct?

I’ve got the rack version, which is amazing. It’s so wide, almost to the point where it sounds like it’s phasing and doing weird things–but maybe mine’s broken! That’s the sound of all the keys from the last three albums, especially Being Funny in a Foreign Language because it has acoustic, sample-based sounds that suit going under a piano.

Are you still using the vintage JUNO-106 in your productions?

The JUNO-106 is versatile and has an amazing low-end, so it’s on most of our recent records. When we go out of the box, it’s usually about chasing imperfection and nuance. You get that from these synths, whether due to the oscillators being old and out of tune, the chorusing, or the tactile process of being able to do things quickly. There are more happy accidents when you mess around with hardware synths, and they have more humanity.

"The legacy of Roland instruments is interesting. They're incredibly influential products that have contributed so much to pop music."

Can you put your finger on what it is about the Roland gear that specifically appeals to you?

I have an obsession with things that are Japanese. If you ever buy a vintage synth from Japan, take it apart and look inside; the standard they maintain is insane. The legacy of Roland instruments is interesting. They’re incredibly influential products that have contributed so much to pop music and other genres.

Back to Basics

Was your latest LP, Being Funny in a Foreign Language, a deliberate attempt to return to basics?

Notes on a Conditional Form was the most experimental album we’d made, but we risked becoming insular or indulgent. We’re never content to stay in one area and want to prove to ourselves and our audience that we can do anything anytime. That’s probably why our records are all over the place. On Being Funny in a Foreign Language, we wanted to make a short, concise record with few rules, albeit not using the same techniques from song to song.

"We're never content to stay in one area and want to prove to ourselves and our audience that we can do anything anytime."

Why did you choose to record at Real World studios?

We knew that we wanted to make an album all in one room, and the main room at Real World is so massive that you can set up a whole backline around its perimeter and keep everything in situ. You can set up ten synths, a drum kit, and a vocal booth, and none of it has to move at any point. So you can choose what to use or play together as a group. In that environment, you learn that speed is everything. When you need to capture a specific moment, even plugging in a power cable can take too long.