“You are now about to witness the strength of street knowledge.” Those words open N.W.A’s Straight Outta Compton, a record that utterly atomized the musical landscape into which it emerged. Around vintage drum breaks paired with a Roland TR-808, the LA-based group brought theretofore unseen levels of rawness and realism into hip-hop. While many of the collective members’ names are sewn into the fabric of rap history (see Dr. Dre, Ice Cube, and Eazy-E), Arabian Prince—born Kim Renard Nazel—was there from the start as N.W.A stared the mainstream in the eye. “We were having a great time,” he recalls of that magical period. “It was kind of like the building of a supergroup.”

Making of a Movement

Speaking from his Los Angeles studio, Arabian Prince has a unique take on the rise of N.W.A. “Everybody thinks it was like this movement, right?” he says. “I always make the joke, like, ‘Man, we were just trying to figure out what we was eating for lunch.’”

He also stresses that, although new to the national stage at that time, most of the group had been cutting their teeth individually in the close-knit Southern California rap world. “Dre was with the World Class Wreckin’ Cru, I was doing my own stuff independently, and Ice Cube was with a group called C.I.A.,” he says. “We all had records out. Only person that had never done a record was Eazy. He was just this cat Dre had met, you know?”

The chemistry of N.W.A was explosive and combustible. The once-in-a-generation collection of talents built a sound that shook parents and thrilled rap’s growing audience. “Dre, me, Yella—we were more on the production side,” Arabian Prince reveals of the group’s unique creative process. “Cube, Ren were more on the writing side. And Eazy was just Eazy.”

In contrast to their East Coast counterparts, the party-ready feel of the music they were concocting emerged from Cali’s endless summer. “West Coast hip-hop was more up-tempo, a little bit more dancey 808 stuff,” he explains. “If you look at our ghetto, places in the hood on the West Coast, we still got palm trees.”

The coastal vibe particularly spread into the lyrics. “Ice Cube wrote ‘Boyz in the Hood’ for some East Coast rappers, but they were like, ‘We don’t know anything about a ’64. What’s a 40 oz.?’” Arabian Prince recalls. “They didn’t know the West Coast slang in the hood, so Dre talked Eazy into rapping the song—he was never a rapper.”

“They didn't know the West Coast slang in the hood, so Dre talked Eazy into rapping the song—he was never a rapper.”

All In the Family

Like all supergroups, the cumulative power was greater than the members predicted—setting the template for future hip-hop dynasties like Wu-Tang Clan and A Tribe Called Quest. But for Arabian Prince, before the rap game was a Compton childhood, for the N.W.A lore reflects his personal background.

“Compton was the good, the bad, and the ugly,” he says. “You had parents who were very supportive, and you had the bad, which was the streets, and you had the ugly, which was my cousins and uncles, who were doing all the bad stuff.”

He credits the support of family members who encouraged him to express his creativity as crucial in keeping him on the right path. Plus, he had a genetic predisposition to the arts from his parents. “My mother was a classical pianist, and my father wrote over 100 books and edited the Urban Network and Cashbox—both music magazines.”

With that kind of pedigree, it wasn’t long before music began creeping into the future prince’s life. “Music was around me always,” he says. “Once my uncles got rehabilitated, they got sent to the military and came back from overseas with electronics.”

At a mere seven years of age, he glimpsed the future in their haul. “My cousin Kenneth opens one suitcase, and it’s a keyboard. Then he opens the other, and it’s a big old mad scientist thing with wires. It was an ARP 2600.”

“As DJs, we were playing everything and watching the reactions of the people. Our music reflected all of that.”

Planet Rock Lobster

The synth-in-a-suitcase experience left an indelible impression, and within a few years, he was in the game—albeit on the schoolyard. “I started DJing parties at my school at 14-15,” he remembers. “I was making little mix tapes, taking them to school, and selling them for lunch money.”

Hip-hop was still in its infancy, and the East Coast was on the ascendant. “We were bringing in rappers from the East Coast to perform, and I thought ‘These dudes look like us, they’re the same age as us, and they’re making records. How can we get in on that?’”

Arabian Prince credits the diverse musical landscape of the era as a key component in the evolution of the West Coast’s take on rap music. “All we had was Top 40 radio, so we were listening to everything from Grace Jones to Depeche Mode, Earth, Wind & Fire.”

Even amid that wild mélange, Arabian Prince’s tastes were idiosyncratic. “It was a melting pot of sound,” he explains. “There was Funkadelic and Michael Jackson, but then there was Devo. The B-52s with ‘Rock Lobster’ was one of my favorite groups.”

He and his cohort were taking it all in, lighting the fuse for what would explode in the dense N.W.A sound collage. “As DJs, we were playing everything and watching the reactions of the people. Our music reflected all of that.”

“We would hang out at Egypt's house, sit in his garage, and just play with the 808.”

Arabian Prince even has a theory about the way certain tracks reshaped the landscape at that time: “I always tell people that 50 or 60% of the influence on hip-hop came from Kraftwerk, because from ‘Numbers’ and ‘Trans-Europe Express,’ you get ‘Planet Rock,’ right?”

Here, the coastal aesthetic divide again enters the conversation. “All the music we had on the West Coast in the early pop-locking days came from Kraftwerk, Parliament Funkadelic, and Prince,” he explains. “That blend created what we called electro funk on the West Coast and what they just called hip-hop on the East.”

808s and Palm Trees

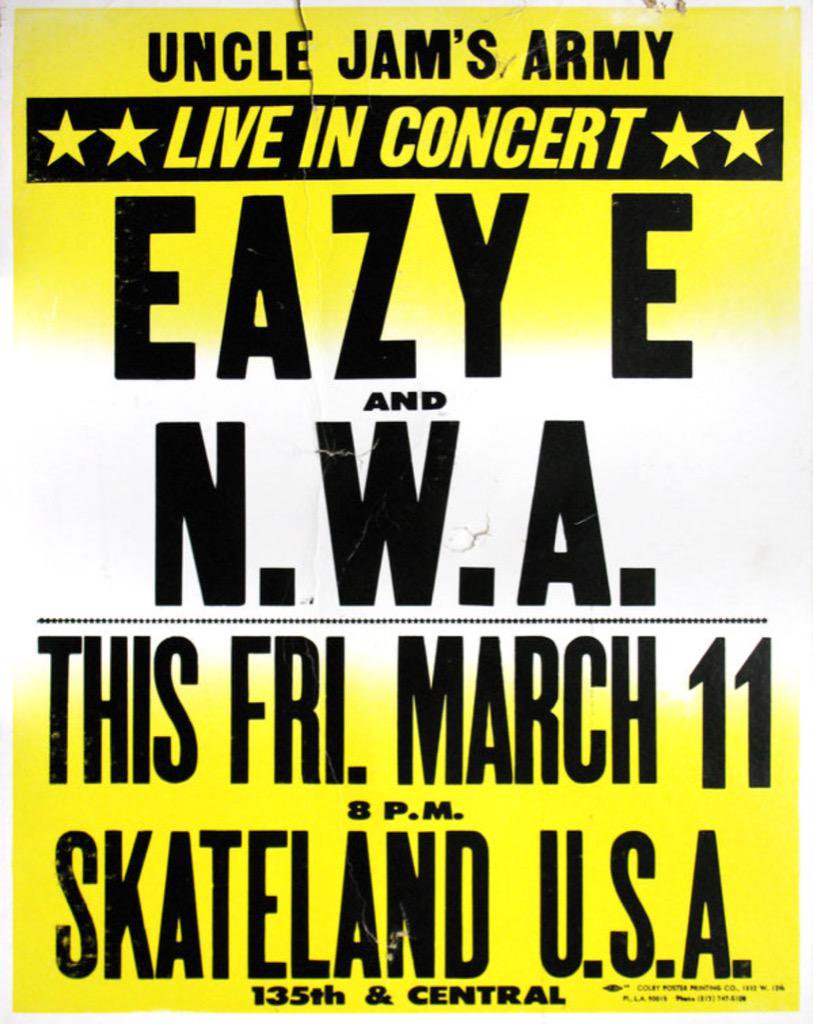

While the idyllic nature of Los Angeles played a part in the new sounds coming from Arabian Prince and his peers, so did a particular Roland drum machine. The TR-808 appeared on the scene and created a booming imprint. “I was doing stuff with a group called Uncle Jamm’s Army and was friends with Egyptian Lover, who had a big DJ crew,” he recalls. “They had an 808 and would take it onstage.”

The device piqued Arabian Prince’s technology bug. “We would hang out at Egypt’s house, sit in his garage, and just play with this thing.”

Soon, watching his friends going into studio and releasing records lit a fire under Arabian Prince to do the same. “I saved up 500 bucks, and a guy who I used to DJ for at a little community center gave me 500 bucks,” he laughs. “The guy in the studio had an 808 and a JUNO-60. We had to use a Doctor Click CV gate to sync it. I still have it in my closet.”

“The guy in the studio had an 808 and a JUNO-60. We had to use a Doctor Click CV gate to sync it. I still have it in my closet.”

Success in Many Forms

Things progressed quickly for the budding producer, and by the time Arabian Prince hooked up with the eclectic N.W.A crew, the moment was ready to meet the new face of hip-hop. With its stark tales of urban reality and layered earworms, the music struck a nerve commercially—1988’s Straight Outta Compton came to define the gangsta rap genre. But the music was deeper than that, even espousing social consciousness on tracks like “Express Yourself.” Still, public perception was hard to shake.

“When we first started touring, we couldn’t go anywhere because it was so controversial,” Arabian Prince explains. “The police were after us. We’d go to certain cities, gangs were after us. They didn’t understand we’re not a gang, we just sound like one.”

The N.W.A story is well-documented, both on paper and film, yet Arabian Prince’s contributions to the group’s golden era are often overlooked. He left the crew early over disagreements with management over financial dealings.

Still, the upbeat artist harbors no resentment, attributing his defection to a lifelong sense of pragmatism. “I moved out when I was like 17,” he shares. “I had my own apartment, my own car. Dre lived at home. Yella lived at home. Ren and Cube lived at home. I had bills.”

“I had my own apartment, my own car. Dre lived at home. Yella lived at home. Ren and Cube lived at home. I had bills.”

In addition, Arabian Prince was already busy exploring other avenues for his production talent. His inspired work on “Supersonic” by J.J. Fad proved another smash hit. “That was a funny one,” he recalls of the 1988 classic. “Me and Dre used to hang out with these girls from Rialto, and they always wanted to make a record.”

He brought them into the studio while working on a track for his Professor X persona. The group spent the bulk of a four-hour session working on a diss track before they tried their hand at a dancey electro number.

“I had an 808 and a DX7—that’s all that was in the studio at the time,” remembers Arabian Prince. “I put down the beat, put a bass line on it, and the girls just made up some stuff. That’s the whole song.“

The song was lightning in a bottle and took off on the radio. “When we released it on Dream Team Records, initially it was the B-side. But when the radio station just got it, we had to go repress it and make it a single.”

“I’ve probably worked on over 100 video game titles in the last 40 years, so I've been in this almost as long as I've been

doing music."

Technology—Always and Forever

One unusual aspect of the Arabian Prince story is his side career in the world of tech. The detour began on the road with N.W.A. “I was in the hotel room a lot and I would always travel with computers, even in the ’80s,” he says. “I had a TRS-80 which was too big to travel with, but I had a Tandy laptop that I got from RadioShack.”

His interest in tech stemmed from foresight. “I taught myself how to code because I really wanted to get into coding video games,” Arabian Prince explains. “As soon as ColecoVision and those early handheld games came out, they wanted to play video games or go to their arcade instead of going to clubs and partying.”

As with music, he observed and strategized how to make his way in. “I eventually snuck my way into the gaming and animation industries through Fox and Fox Interactive,” he says. “I worke on the first Power Rangers, Silver Surfer, and The Addams Family doing animation, not even music.”

What started as a side quest became much more, and Arabian Prince now has an entire gaming history alongside his musical one. “I’ve probably worked on over 100 video game titles in the last 40 years, so I’ve been in this almost as long as I’ve been doing music.”

“If you only got one kind of sound as an artist, it's hard to make 32 different beats within your genre. The three personas help me split it up.”

SpongeBob, 808 Day, and The Future

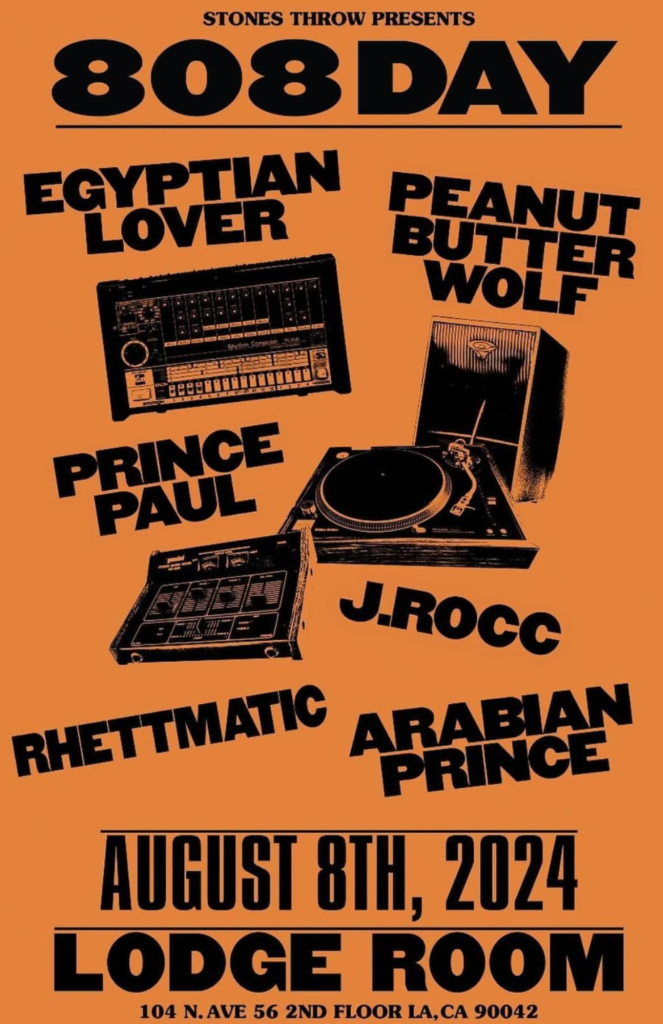

Flash forward to the present day: Arabian Prince has created his “TR-808 Arabian Prince” collection for Roland Cloud to celebrate 808 Day. “It has 32 kits of the 808 and 32 patterns on the 808 with multiple sequences in the pattern.”

The collection reflects what he sees as a trifecta of sonic identities. “I have my gangster rap, old-school hip-hop sound, I have my electro funk sound, and then I have my Professor X sound, which is more Kraftwerk-y,” he explains. “If you only got one kind of sound as an artist, it’s hard to make 32 different beats within your genre. The three personas help me because I can split it up.”

These days, Arabian Prince is in his happy place, surrounded by decades-worth of gear and a space-age lighting theme. The sci-fi atmosphere aligns with the video game and animation work he’s been doing alongside his music production since his early days. “A lot of people don’t even know I was in N.W.A,” he says with a smile. “I’m a self-proclaimed Willy Wonka, a self-proclaimed SpongeBob.”

Even with his legendary status, he remains focused on creativity and the task at hand. The promise of the next discovery is what keeps the Arabian Prince questing. “I’m a technologist. The future is for me. Fame, I could care less about. I want to work. I’m a worker.”